3. GUIDELINE

3.1. Thromboprophylaxis post-surgery

3.1.1. Introduction

This guideline provides procedure and patient risk-specific guidance weighing the benefit of reduced VTE with the harm of increased bleeding. The Panel provides recommendations for numerous urologic procedures with a simple and practical patient risk stratification scheme.

3.1.2. Outcomes and definitions

The Panel defined non-fatal and fatal symptomatic VTE and non-fatal and fatal major bleeding as key outcomes. Venous thromboembolism was defined as symptomatic DVT or PE and major bleeding was defined as bleeding requiring re-operation or intervention (such as angioembolisation). Transfusion, indwelling catheter, or change in hemoglobin levels were not considered as part of “major bleeding”.

3.1.3. Timing and duration of thromboprophylaxis

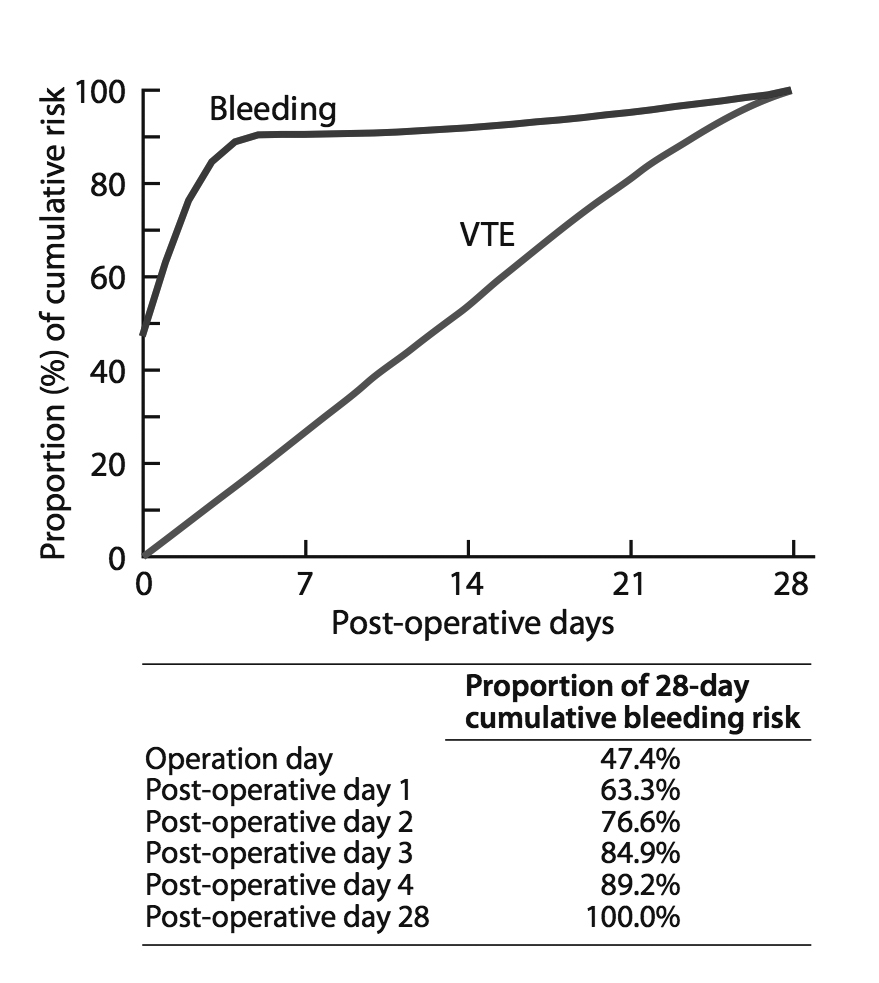

High-quality evidence suggests that, of the cumulative risk during the first four weeks post-surgery, approximately 50% of major bleeds occur between surgery and the next morning and approximately 90% during the first four post-surgical days. In contrast, the risk of VTE is almost constant during these first four post-surgical weeks (Figure 1) [1,13-15].

There are no direct comparisons of the same agent administered before versus after surgery. Recent studies with direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in orthopedic surgery have, however, suggested that, relative to starting low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) before surgery, prophylaxis can begin 24 hours after surgery without an increase in VTE but with a decrease in bleeding complications [16,17]. Given these findings, in addition to the compelling rationale regarding the relative timing of bleeds versus thrombosis (Figure 1), we recommend administration of thromboprophylaxis beginning the day after surgery.

One could argue that prophylaxis be started even later than this, especially in procedures with high bleeding risk. The extent to which an even later start would decrease the effectiveness of thromboprophylaxis is, however, open to question. Given that the further the patient is from surgery the greater the net benefit of prophylaxis (as bleeding risks decreases), while the risk of VTE is just as great in the fourth week after surgery as in the first, the optimal duration of pharmacological prophylaxis is approximately four weeks

post-surgery [1,13-15].

Figure 1: Proportion of cumulative risk (%) of VTE and major bleeding by week since surgery during the first four post-operative weeks

Figure modified from: Tikkinen KA, et al. Systematic reviews of observational studies of risk of thrombosis and bleeding in urological surgery (ROTBUS): introduction and methodology. Syst Rev 2014;3:150. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

3.1.4. Basic principles for recommending (or not recommending) post-surgery thromboprophylaxis

Considerations in the administration of thromboprophylaxis include the relative effect of prophylaxis on key outcomes, baseline risk of key outcomes, as well as patient-related risk (and protective) factors. Finally, one must consider the quality of evidence (certainty in estimates) as well as the relative importance of the relevant outcomes.

3.1.4.1. Effect of prophylaxis on key outcomes

The Panel performed several meta-analyses of RCTs in urology, general surgery, gynecology, and gastrointestinal surgery to inform relative risk estimates of thromboprophylaxis [1,8,9]. These meta-analyses demonstrated that anticoagulants (such as LMWH) reduce the relative risk of VTE by approximately 50% and increase the relative risk of major bleeding by approximately 50% [1,8,9]. These meta-analyses also demonstrated 50% VTE risk reduction for mechanical prophylaxis [1,8,9]. An earlier meta-analysis informing the risk estimates for direct-acting oral anticoagulants yielded similar estimates: a decrease in the relative risk of VTE by approximately 50% and an increase of major bleeding by approximately 50% [18]. The evidence regarding pharmacological prophylaxis was judged as high-quality but low-certainty for mechanical prophylaxis because studies used surrogate outcomes, had very few events, unblinded patients and assessors, and provided almost no information on intermittent pneumatic compression (low-quality evidence) [1,8,9].

3.1.4.2. Baseline risk of key outcomes

The Panel performed a series of systematic reviews to provide estimates of absolute risk of symptomatic VTE and bleeding requiring re-operation in urologic surgery [1,8,9]. The cited publications, with minor modifications, provide the evidence summary used to develop these recommendations.

3.1.4.3. Patient-related risk (and protective) factors

The Panel conducted a comprehensive literature search addressing VTE and bleeding risk factors in the context of urology, general surgery, gynecology, and gastro intestinal surgery [1]. A model was developed for VTE risk based on the studies reporting the most relevant and high-quality evidence [19-27] (Table 1). However, this model has not been validated and clinicians may consider other factors, including the length of the surgical procedure, oral contraception, immobility, spinal cord injury, and inheritable blood disorders such as antiphospholipid antibody syndromes, factor V Leiden, antithrombin, protein C or S deficiencies, when making decisions. The Panel’s search did not reveal studies demonstrating convincing and replicable risk factors for bleeding [1]; therefore, bleeding risk was not stratified by patient specific factors.

Table 1: Venous thromboembolism (VTE) according to patient risk factors

Risk | Likelihood of VTE | |

Low risk | No risk factors | 1x |

Medium risk | Any one of the following: age 75 years or more; Body mass index 35 or more; VTE in 1st degree relative (parent, full sibling, or child). | 2x |

High risk | Prior VTE Patients with any combination of two or more risk factors | 4x |

3.1.4.4. From evidence to recommendations

When creating recommendations, the Panel first calculated the net benefit (absolute reduction in VTE risk – absolute increase in bleeding risk) and thereafter considered quality of evidence, separately for both pharmacological and mechanical prophylaxis. The Panel made strong recommendations only if the quality of evidence was moderate or high and net benefit fulfilled threshold criteria (see below); otherwise, the Panel made weak recommendations.

When calculating the net benefit, twice the weight was assigned for major bleeding as for ‘any symptomatic VTE’. The most comprehensive guideline published in the field, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guideline on “Prevention of VTE in Nonorthopedic Surgical Patients” considered symptomatic VTE and major bleeding as having the same weight. However, they included transfusions in their definition of major bleeding [28] which the Panel considered less relevant because: 1) studies often did not report transfusions, 2) criteria for transfusion vary widely between studies, and use of transfusion may have limited relation to underlying bleeding, and 3) transfusions are less important to patients than are reoperations. Given this guideline’s focus on only the more severe bleeds – those that require re-operation – the greater weight on preventing bleeding is appropriate.

For each procedure (and separately for each patient risk factor stratum), the net benefit of using pharmacological thromboprophylaxis (benefit from VTE reduction – harm from bleeding) was calculated. After considering the net benefit and quality of evidence, the thresholds presented in Table 2 were indentified.

Table 2: Thresholds of net benefit and quality of evidence used when creating recommendations

Net benefit* | Recommendation | Note |

Pharmacological prophylaxis | ||

> 10 per 1000 | STRONG in FAVOUR | If based on moderate or high-quality evidence |

> 10 per 1000 | WEAK in FAVOUR | If based on low or very low-quality evidence |

> 5-10 per 1000 | WEAK in FAVOUR | In borderline situations prophylaxis was always favoured as case fatality is higher for VTE than for bleeding [8,9] |

> 1-5 per 1000 | WEAK AGAINST | |

< 1 per 1000 | WEAK AGAINST | If based on low or very low-quality evidence |

< 1 per 1000 | STRONG AGAINST | If based on moderate or high-quality evidence |

Mechanical prophylaxis | ||

> 2.5 per 1000 | WEAK in FAVOUR | |

< 2.5 per 1000 | WEAK AGAINST | |

* Net benefit is equal to absolute reduction in VTE risk minus absolute increase in bleeding risk (with twice the weight for major bleeding as for VTE). The net benefit is positive when the value of reduced VTE is greater than increased bleeding.

These thresholds reflect value and preference considerations for which there is limited evidence available [29]. A recent multinational study found that the median threshold net benefit at which women with a history of VTE were willing to accept use of heparin to prevent VTE during pregnancy or the post-partum period is 30 in 1,000 [30]. In that study, the use of prophylaxis spanned the entire duration of pregnancy and continued during the post-partum period. As post-surgery prophylaxis has a much shorter duration, and is thus less burdensome, our threshold of strong recommendation when net benefit is 10 in 1,000 or more is consistent with this evidence. As mechanical prophylaxis is typically used for a shorter duration than the Panel recommend for pharmacological prophylaxis [31], a lower threshold for mechanical prophylaxis was used.

Making a recommendation regarding thromboprophylaxis requires trading off VTE reduction against bleeding increase, and thus placing a relative value on the two events. A serious bleed (defined as bleeding requiring re-operation or intervention) was considered twice as important as a VTE (defined as symptomatic DVT or PE) event. For patients who feel very differently about this relative value judgment, the Panel’s recommendations may not be optimal.

3.1.5. General statements for all procedure-specific recommendations

Consistent with GRADE guidance [32], a single good practice statement was made in which the supporting evidence is compelling, though indirect, and which was not summarised systematically. This association between early ambulation and decreased post-operative complications, in particular decrease in VTE, and early discharge from hospital is convincing. Further, early ambulation has no important adverse consequences. Therefore, the Panel believes that early ambulation for all patients after surgery represents good clinical practice.

The following apply to all recommendations for pharmacologic prophylaxis:

All recommendations are based on a starting time of the morning after surgery.

The optimal duration of prophylaxis for all recommendations is approximately four weeks

post-surgery.

There are number of acceptable alternatives for pharmacologic prophylaxis (Table 3).

Table 3: Alternative regimens for pharmacological prophylaxis

Pharmacological agent | Dosage* |

Low molecular weight heparins: | |

Dalteparin | 5,000 IU injection once a day |

Enoxaparin | 40 mg injection once a day |

Tinzaparin | 3,500/4,500 IU injection once a day |

Unfractionated heparin | 5,000 IU injection two or three times a day |

Fondaparinux† | 2.5 mg injection once a day |

Direct acting oral anticoagulants†: | |

Dabigatran | 220 mg tablet once a day |

Apixaban | 2.5 mg tablet once a day |

Edoxaban | 30 mg tablet once a day |

Rivaroxaban | 10 mg tablet once a day |

* Dosages may not apply in renal impairment.

† Fondaparinux and direct acting oral anticoagulants have not been sufficiently studied in urology to warrant on-label use for post-surgery thromboprophylaxis.

3.1.6.Recommendations

Ambulatory day surgery

R1. In all patients undergoing minor ambulatory day surgery (for example, circumcision, hydrocelectomy and vasectomy), the Panel recommends against use of pharmacological prophylaxis (strong, moderate-quality evidence), and against use of mechanical prophylaxis (strong, moderate-quality evidence).

Note: The Panel is of the opinion that these patients have risk of VTE close to the general population with an increased risk of bleeding.

Open radical cystectomy

R2. In all patients undergoing open radical cystectomy, the Panel recommends use of pharmacological prophylaxis (strong, moderate or high-quality evidence), and suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, low-quality evidence).

Robotic radical cystectomy

R3. In all patients undergoing robotic radical cystectomy, the Panel suggests use of pharmacological prophylaxis (weak, low-quality evidence), and suggest use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, low-quality evidence).

Table 4: Procedure-specific evidence summaries with recommendations for radical cystectomies

Procedure | Outcome | Baseline risk among | Net benefit per | Certainty in | Recommendations for pharmacological | Recommendations for mechanical prophylaxis | |

Cystectomy, Open | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 29 | 13 | Moderate | Strong, for | Weak, for |

Medium- risk | 58 | 27 | High | Strong, for | Weak, for | ||

High risk | 116 | 56 | High | Strong, for | Weak, for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 3.0 | Moderate/High | |||||

Cystectomy, Robotic | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 26 | 11 | Low | Weak, for | Weak, for |

Medium-risk | 52 | 24 | Low | Weak, for | Weak, for | ||

High risk | 103 | 50 | Low | Weak, for | Weak, for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 3.0 | Low | |||||

* Net benefit is equal to absolute reduction in VTE risk minus absolute increase in bleeding risk (with twice the weight for major bleeding as for VTE). For instance, in medium-risk patients undergoing open radical cystectomy, use of pharmacological prophylaxis, such as LMWH, beginning first post-surgery day for four weeks decreases absolute risk of VTE by 29 per 1,000 and increases absolute risk of bleeding by 0.8 per 1,000 (Figure 1). As twice the weight for major bleeding was assigned as for VTE, the net benefit is 27 per 1,000.

Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy

R4. For patients undergoing laparoscopic radical prostatectomy without pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND), for those at low risk of VTE, the Panel recommends against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (strong, moderate-quality evidence) and suggests against use of mechanical prophylaxis (weak, low-quality evidence); for those at moderate and high risk, the Panel suggests against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, moderate or high quality evidence) and suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, low-quality evidence).

R5. For patients undergoing laparoscopic radical prostatectomy with standard PLND, for those at low risk of VTE, the Panel recommends against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (strong, moderate-quality evidence); for those at medium risk, the Panel suggests against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, moderate-quality evidence); for those at high risk, the Panel recommends use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (strong, high-quality evidence); and for all patients, the Panel suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, low-quality evidence).

R6. For patients undergoing laparoscopic radical prostatectomy with extended PLND, for those at low risk of VTE, the Panel suggests against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, moderate-quality evidence); for those at medium risk, the Panel suggests use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, high-quality evidence); for those at high risk, the Panel recommends use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (strong, high-quality evidence); and for all patients, the Panel suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, low-quality evidence).

Open radical prostatectomy

R7. For patients undergoing open radical prostatectomy without PLND or with standard PLND, for those at low risk of VTE, the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis is suggested (weak, moderate-quality evidence); for those at medium and high risk, the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis is recommended (strong, moderate or high-quality evidence); and for all patients, the Panel suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, low-quality evidence).

R8. For all patients undergoing open radical prostatectomy with extended PLND, the Panel recommends use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (strong, moderate or high-quality evidence), and suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, low-quality evidence).

Robotic radical prostatectomy

R9. For patients undergoing robotic radical prostatectomy without PLND, for those at low risk of VTE, the Panel recommends against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (strong, moderate-quality evidence) and suggests against use of mechanical prophylaxis (weak, low-quality evidence); for those at medium and high risk, the Panel suggests against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, moderate-quality evidence) and suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, low-quality evidence).

R10. For patients undergoing robotic radical prostatectomy with standard PLND, for those at low risk of VTE, the Panel recommends against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (strong, moderate-quality evidence); for those at medium risk, the Panel suggests against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, moderate-quality evidence); for those at high risk, the Panel suggests use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, moderate-quality evidence); and for all patients, the Panel suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, low-quality evidence).

R11. For patients undergoing robotic radical prostatectomy with extended PLND, for those at low risk of VTE, the Panel suggests against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, moderate-quality evidence); for those at medium risk, the Panel suggests use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, moderate-quality evidence); for those at high risk, the Panel recommends use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (strong, moderate-quality evidence); and for all patients, the Panel suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, low-quality evidence).

Table 5: Procedure-specific evidence summaries with recommendations for radical prostatectomies

Procedure | Outcome | Baseline risk | Net benefit per | Certainty in estimate | Recommendations for pharmacological prophylaxis | Recommendations for mechanical prophylaxis | |

Prostatectomy, Laparoscopic without pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 4.0 | -1.7 | Moderate | Strong - against | Weak – against |

Medium-risk | 8.0 | 0.30 | Moderate | Weak - against | Weak - for | ||

High-risk | 15 | 4.0 | High | Weak - against | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 7.0 | Moderate | |||||

Prostatectomy, Laparoscopic with standard PLND | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 8.0 | -1.3 | Moderate | Strong - against | Weak - for |

Medium-risk | 15 | 2.2 | Moderate | Weak - against | Weak - for | ||

High-risk | 30 | 10 | High | Strong - for | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 10 | Moderate | |||||

Prostatectomy, Laparoscopic with extended PLND | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 15 | 0.10 | Moderate | Weak - against | Weak - for |

Medium-risk | 30 | 7.6 | High | Weak - for | Weak - for | ||

High-risk | 60 | 23 | High | Strong - for | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 14 | Moderate | |||||

Prostatectomy, Open without PLND | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 10 | 4.5 | Moderate | Weak - for | Weak - for |

Medium-risk | 20 | 9.5 | Moderate | Strong - for | Weak – for | ||

High-risk | 39 | 19 | High | Strong - for | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 1.0 | Moderate | |||||

Prostatectomy, Open with standard PLND | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 20 | 8.9 | Moderate | Weak – for | Weak - for |

Medium-risk | 39 | 18 | High | Strong - for | Weak - for | ||

High-risk | 79 | 38 | High | Strong -for | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 2.0 | Moderate | |||||

Prostatectomy, Open with extended PLND | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 39 | 18 | Moderate | Strong - for | Weak - for |

Medium-risk | 79 | 38 | High | Strong - for | Weak - for | ||

High-risk | 157 | 77 | High | Strong - for | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 2.0 | Moderate | |||||

Prostatectomy, Robotic without PLND | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 2.0 | -1.1 | Moderate | Strong - against | Weak - against |

Medium-risk | 5.0 | 0.40 | Moderate | Weak - against | Weak - for | ||

High-risk | 9.0 | 2.4 | Moderate | Weak - against | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 4.0 | Moderate | |||||

Prostatectomy, Robotic with standard PLND | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 5.0 | -0.7 | Moderate | Strong - against | Weak - for |

Medium-risk | 9.0 | 1.3 | Moderate | Weak - against | Weak - for | ||

High-risk | 19 | 6.3 | Moderate | Weak - for | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 6.0 | Moderate | |||||

Prostatectomy, Robotic with extended PLND | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 9.0 | 0.3 | Moderate | Weak - against | Weak - for |

Medium-risk | 19 | 5.3 | Moderate | Weak - for | Weak - for | ||

High-risk | 37 | 14 | Moderate | Strong - for | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 8.0 | Moderate | |||||

Nephrectomy

R12. For patients undergoing laparoscopic partial nephrectomy, for those at low and medium-risk of VTE, the Panel suggests against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, low-quality evidence); for those at high risk, the Panel recommends use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (strong, moderate-quality evidence); and for all patients, the Panel suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, low-quality evidence).

R13. For all patients undergoing open partial nephrectomy, the Panel suggests use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, very low-quality evidence), and suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, very low-quality evidence).

R14. For patients undergoing robotic partial nephrectomy, for those at low risk of VTE, the Panel suggests against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, moderate-quality evidence); for those at medium risk, the Panel suggests use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, moderate-quality evidence); for those at high risk, the Panel recommends use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (strong, high-quality evidence); and for all patients, the Panel suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, low-quality evidence).

R15. For patients undergoing laparoscopic radical nephrectomy, for those at low or medium risk of VTE, the Panel suggests against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, very low-quality evidence); for those at high risk, the Panel suggests use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, very low-quality evidence); and for all patients, the Panel suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, very low-quality evidence).

R16. For patients undergoing open radical nephrectomy, the Panel suggests use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, very low-quality evidence); and for all patients, the Panel suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, low-quality evidence).

R17. For all patients undergoing radical nephrectomy with thrombectomy, the Panel suggests use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, very low-quality evidence), and suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, very low-quality evidence).

R18. For all patients undergoing open nephroureterectomy, the Panel suggests use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, very low-quality evidence), and suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, very low-quality evidence).

Table 6: Procedure-specific evidence summaries with recommendations for kidney procedures for cancer

Procedure | Outcome | Baseline risk among | Net benefit per | Certainty in | Recommendations | Recommendations | |

Nephrectomy, Laparoscopic partial | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 11 | -3.4 | Low | Weak - against | Weak – for |

Medium-risk | 21 | 1.6 | Low | Weak - against | Weak – for | ||

High-risk | 42 | 12 | Moderate | Strong - for | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 17 | Low/Moderate | |||||

Nephrectomy, Open partial | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 10 | 4.5 | Very low | Weak - for | Weak – for |

Medium-risk | 20 | 9.5 | Very low | Weak - for | Weak – for | ||

High-risk | 39 | 19 | Very low | Weak - for | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 1.0 | Moderate | |||||

Nephrectomy- Robotic partial | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 10 | 2.4 | Moderate | Weak - against | Weak – for |

Medium-risk | 19 | 6.9 | Moderate | Weak - for | Weak – for | ||

High-risk | 39 | 17 | high-quality | Strong - for | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 5.0 | Moderate | |||||

Nephrectomy, Laparoscopic radical | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 7.0 | 0.9 | Very low | Weak - against | Weak – for |

Medium-risk | 13 | 3.9 | Very low | Weak - against | Weak – for | ||

High-risk | 26 | 10 | Very low | Weak - for | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 5.0 | Very low | |||||

Nephrectomy, Open radical | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 11 | 5.2 | Low | Weak - for | Weak – for |

Medium-risk | 22 | 11 | Low | Weak - for | Weak – for | ||

High-risk | 44 | 22 | Low | Weak - for | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 0.5 | Very low | |||||

Radical nephrectomy with thrombectomy | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 29 | 4.0 | Very low | Weak - for | Weak - for |

Medium-risk | 58 | 19 | Very low | Weak - for | Weak - for | ||

High-risk | 116 | 48 | Very low | Weak - for | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 20 | Very low | |||||

Open nephroureterectomy | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 16 | 7.7 | Very low | Weak - for | Weak - for |

Medium-risk | 31 | 15 | Very low | Weak - for | Weak - for | ||

High-risk | 62 | 31 | Very low | Weak - for | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 0.5 | Very low | |||||

R19. For all patients undergoing primary nerve sparing RPLND, the Panel suggests use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, very low-quality evidence), and suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, very low-quality evidence).

Table 7: Procedure-specific evidence summaries with recommendations for primary nerve sparing retroperitoneal lymph node dissection

Procedure | Outcome | Baseline risk among | Net benefit per | Certainty | Recommendations | Recommendations | |

Primary nerve sparing retroperitoneal lymph node dissection | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 23 | 10 | Very low | Weak - for | Weak – for |

Medium-risk | 45 | 21 | Very low | Weak - for | Weak – for | ||

High-risk | 91 | 44 | Very low | Weak - for | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 2.0 | Very low | |||||

Non-cancer urological procedures

R20. For all patients undergoing transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) or equivalent procedures, the Panel suggests against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, very low-quality evidence); for those at low or medium risk of VTE, the Panel suggests against use of mechanical prophylaxis (weak, low-quality evidence); and for those at high risk, the Panel suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, low-quality evidence).

R21. For patients undergoing laparoscopic donor nephrectomy or open donor nephrectomy, for those at low risk of VTE, the Panel suggests against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, very low or low-quality evidence), and suggests against use of mechanical prophylaxis (weak, very low or low-quality evidence); for medium risk patients, the Panel suggests against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, very low or low-quality evidence), and suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, very low or low-quality evidence); and for high risk patients, the Panel suggests use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, very low or low-quality evidence), and suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, very low or low-quality evidence).

R22. For all patients undergoing open prolapse surgery or reconstructive pelvic surgery, the Panel suggests against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, very low-quality evidence); for those at low or medium risk of VTE, the Panel suggests against use of mechanical prophylaxis (weak, very low or low-quality evidence); while for those at high risk, the Panel suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, very low or low-quality evidence).

R23. For all patients undergoing percutaneous nephrolithotomy, the Panel suggests against use of pharmacologic prophylaxis (weak, very low-quality evidence); for those at low or medium risk of VTE, the Panel suggests against use of mechanical prophylaxis (weak, very low-quality evidence); while for those at high risk, the Panel suggests use of mechanical prophylaxis until ambulation (weak, very low-quality evidence).

Table 8: Procedure-specific evidence summaries (with recommendations) for non-cancer procedures

Procedure | Outcome | Baseline risk among | Net benefit per | Certainty | Recommendations | Recommendations | |

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) or equivalent | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 2.0 | -0.1 | Low | Weak - against | Weak - against |

Medium-risk | 4.0 | 0.9 | Low | Weak - against | Weak - against | ||

High-risk | 8.0 | 2.9 | Low | Weak - against | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 2.0 | Very low | |||||

Donor nephrectomy, laparoscopic | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 4.0 | 1.5 | Low | Weak - against | Weak – against |

Medium-risk | 7.0 | 3.0 | Low | Weak - against | Weak – for | ||

High-risk | 14 | 6.5 | Low | Weak - for | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 1.0 | Low | |||||

Donor nephrectomy, open | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 3.0 | 1.0 | Very low | Weak - against | Weak – against |

Medium-risk | 7.0 | 3.0 | Very low | Weak - against | Weak – for | ||

High-risk | 13 | 6.0 | Very low | Weak - for | Weak – for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 1.0 | Very low | |||||

Recipient nephrectomy, open | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 13 | -5.6 | Very low | Weak - against* | Weak - for |

Medium-risk | 27 | 1.4 | Very low | Weak - against* | Weak – for | ||

High-risk | 53 | 14 | Very low | Weak – for* | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 23 | Very low | |||||

Prolapse surgery, open | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 2.0 | -1.1 | Low | Weak - against | Weak – against |

Medium-risk | 3.0 | -0.6 | Low | Weak - against | Weak – against | ||

High-risk | 7.0 | 1.4 | Low | Weak - against | Weak – for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 4.0 | Very low | |||||

Reconstructive pelvic surgery (including sling surgery for stress urinary incontinence and vaginal prolapse surgery) | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 1.0 | -1.1 | Very low | Weak - against | Weak – against |

Medium-risk | 3.0 | -0.1 | Very low | Weak - against | Weak – against | ||

High-risk | 5.0 | 0.9 | Very low | Weak - against | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 3.0 | Very low | |||||

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy | Venous thromboembolism | Low-risk | 2.0 | -3.7 | Very low | Weak - against | Weak – against |

Medium-risk | 4.0 | -2.7 | Very low | Weak - against | Weak – against | ||

High-risk | 7.0 | -1.2 | Very low | Weak - against | Weak - for | ||

Bleeding requiring reoperation | 9.0 | Low | |||||

* The Panel understands that patients will receive anticoagulation in the peri-operative period. The recommendations against refer to extended prophylaxis.

3.2. Peri-operative management of antithrombotic agents in urology

3.2.1. Introduction

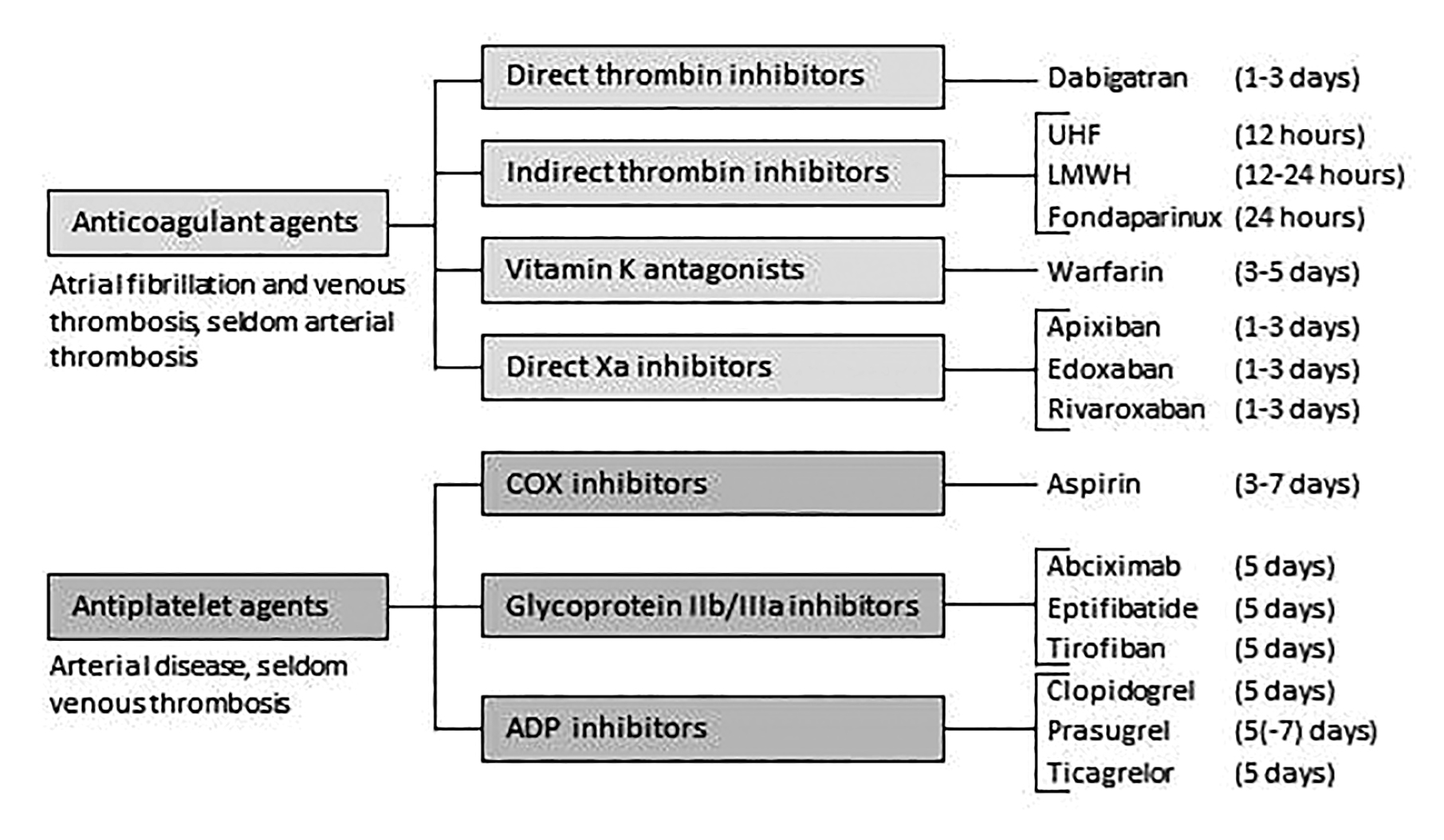

In principle, there are four options to manage use of antithrombotic agents (Figure 2) during the peri-operative period: 1) to defer surgery until antithrombotic agents are not needed, 2) stop antithrombotic agents prior to surgery and restart some time after surgery, 3) continue through the surgical procedure, or 4) administer alternative antithrombotic agents that may still reduce the risk of thrombosis but with less risk of bleeding than agents patients are currently using (“bridging”).

Figure 2: The most widely used antithrombotic agents in patients undergoing urologic surgery Required period of stopping drug before surgery (if desired) provided in parentheses.

3.2.2. Evidence summary

Earlier major guidelines addressing perioperative management of antithrombotic agents in surgery [2,33-35] preceded recent major studies, including large, rigorous randomised trials [15,36-38]. With respect to anti-platelet agents, a recent large, rigorous randomised trial comparing aspirin to placebo has demonstrated that aspirin increases post-operative bleeding without reducing arterial thrombotic events [15]. These results provide indirect evidence for antiplatelet agents other than aspirin. Although the absence of large, rigorous placebo-controlled trials to inform recommendations for other antiplatelet agents constitutes a limitation, given similar antithrombotic and bleeding profiles, the indirect evidence provides useful information to inform our recommendations.

Recommendations that preceded the recent much higher-quality evidence often recommended, in the peri-operative context, substitution of alternative agents for the antithrombotic agents patients were using on a regular basis [39]. The recent evidence has demonstrated that bridging increases bleeding without preventing thrombosis. The Panel therefore essentially have two recommendations for patients receiving antithrombotic agents regularly and contemplating surgery: 1) discontinue antithrombotic therapy for the period around surgery, or 2) in those with a temporary very high risk of thrombosis, delay surgery until that risk decreases. If it is not possible to delay, continuing antithrombotic therapy or bridging through surgery may be advisable.

3.2.3. Recommendations

Five days is an appropriate time to stop antiplatelet agents before surgery while the optimal time to stop varies across anticoagulants (for details, see Figure 2).

R24. In all patients receiving antiplatelet agents (aspirin, clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticagrelor), except those with very high risk of thrombosis (see recommendations 26 and 27), the Panel recommends stopping antiplatelet agents before surgery and not initiating any alternative antithrombotic therapy (strong, high-quality evidence).

R25. In patients in whom antiplatelet agents have been stopped before surgery, the Panel recommends restarting when bleeding is no longer a serious risk – typically four days post-surgery – rather than withholding for longer periods (strong, moderate-quality evidence).

R26. In patients with very high risk of thrombosis receiving antiplatelet agents (those with: drug-eluting stent placement within six months; bare metal stent placement within six weeks; transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke within 30 days) in whom surgery can be delayed, the Panel recommends delaying surgery (strong, high-quality evidence).

R27. In patients with very high risk of thrombosis receiving antiplatelet agents (those with: drug-eluting stent placement within six months; bare metal stent placement within six weeks; TIA or stroke within 30 days) in whom surgery cannot be delayed, the Panel suggests continuing the drugs through surgery (weak, low-quality evidence).

R28. In all patients receiving anticoagulant agents (unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin, warfarin, fondaparinux, dabigatran, apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban), except those with very high risk of thrombosis (see recommendation 26), the Panel recommends stopping drugs before surgery (see Figure 2) and not initiating any alternative antithrombotic therapy (strong, high-quality evidence).

Note: Patients with creatinine clearance < 30 ml/min should not receive dabigatran, apixaban, rivaroxaban or edoxaban.

R29. In patients in whom anticoagulants have been stopped before surgery, the Panel recommends restarting when bleeding is no longer a serious risk – typically four days post-surgery – rather than withholding for longer periods (strong, moderate-quality evidence).

R30. In patients with a new VTE, it is recommended that surgery is delayed for at least one month, and if possible three months, to permit discontinuation of anticoagulation pre-operatively, rather than operating within one month of thrombosis (strong, high-quality evidence).

R31. In patients receiving any anticoagulant with a severe thrombophilia, such as antithrombin deficiency and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, the Panel suggests anticoagulation with either heparin or low molecular weight heparin through surgery, rather than stopping anticoagulation before and after surgery (weak, low-quality evidence).

R32. In patients with high-risk mechanical prosthetic heart valves, such as cage-ball valves, receiving warfarin, the Panel recommends bridging with LMWH prior and subsequent to surgery, rather than discontinuing anticoagulation peri-operatively (strong, high-quality evidence).

Anticoagulation in these patients involves stopping the warfarin five days prior, commencing LMWH four days prior, omitting LMWH on the day of surgery, and recommencing LMWH and warfarin after surgery.