5. MANAGEMENT OF ERECTILE DYSFUNCTION

5.1. Definition and classification

Penile erection is a complex physiological process that involves integration of both neural and vascular events, along with an adequate endocrine milieu. It involves arterial dilation, trabecular smooth muscle relaxation and activation of the corporeal veno-occlusive mechanism [272]. Erectile dysfunction is defined as the persistent inability to attain and maintain an erection sufficient to permit satisfactory sexual performance [273]. Erectile dysfunction may affect psychosocial health and have a significant impact on the QoL of patients and their partner’s [209,274-276].

There is established evidence that the presence of ED increases the risk of future CV events including myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular events, and all-cause mortality, with a trend towards an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality [277]. Therefore, ED can be an early manifestation of coronary artery and peripheral vascular disease and should not be regarded only as a QoL issue, but also as a potential warning sign of CVD [278-281]. A cost analysis showed that screening men presenting with ED for CVD represents a cost-effective intervention for secondary prevention of both CVD and ED, resulting in substantial cost savings relative to identification of CVD at the time of presentation [282].

Erectile dysfunction is commonly classified into three groups based on aetiology: organic, psychogenic and mixed ED. However, this classification should be used, with caution as most cases are actually of mixed aetiology. It has therefore been suggested to use the terms “primary organic” or “primary psychogenic”.

5.2. Risk factors

Erectile dysfunction is associated with unmodifiable and modifiable common risk factors including age, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, CVD, BMI/obesity/waist circumference, MetS, hyperhomocysteinemia, lack of exercise, and smoking, understood as both cigarette smoke and Electronic Nicotine Delivery Devices (ENDS), with a clearly demonstrated positive dose-response association between quantity and duration of smoking [275,279,283-292]. Furthermore, an association between ED status and pharmaco-therapeutic agents for CVD (e.g., thiazide diuretics and β-blockers, except nebivolol), exert detrimental effects on erectile function, whereas newer drugs (i.e., angiotensin-converting enzyme-inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor-blockers and calcium-channel-blockers) have neutral or even beneficial effects [279,293,294]. Furthermore, the use of psychotropic drugs increases the risk of developing ED [295]. Atrial fibrillation [296], hyperthyroidism [51], vitamin D deficiency [297,298], hyperuricemia [299], folic acid deficiency [300], depression [301] and anxiety disorders [302], chronic kidney disease [290], rheumatic disease [303], stroke [304] and COPD [305], migraine (especially in patients aged < 40 years [306], inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have also been reported as risks factors [307]. Available data do not confirm a clear association between ED and hypothyroidism and hyperprolactinaemia [51]. Interestingly, a dual (cause-effect) association between ED and osteoporosis had been proposed, and therefore ED patients should be evaluated by bone mineral density or men with osteoporosis should be further assessed for erectile function [308]. Current evidence supports the fact that renal transplantation improves erectile function and the risk of ED is progressively reduced from before to after surgery [309,310].

Further epidemiological data have also highlighted other potential risk factors associated with ED including sleep disorders [311], obstructive sleep apnoea [312], psoriasis [313-315], gouty arthritis [311] and ankylosing spondylitis [316], non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [317], other chronic liver disorders [318], chronic periodontitis [319], open-angle glaucoma [320], chronic fatigue syndrome [321] and allergic rhinitis [322], and spina bifida [323]. A growing body of evidence has demonstrated an association between the onset of new ED in men who had COVID-19 [324-327]. Similarly, although currently available data are scarce, a positive correlation between cycling and ED had been proposed, even if only after adjusting for age and several comorbidities [328]. Recent findings show that pelvic ring fractures are associated with onset of ED with important influence on QoL, especially in young patients [329,330].

A recent meta-analysis showed that men partnered with women suffering from Female Sexual Dysfunction (FSD) present an increased risk of developing sexual impairment, mostly erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction [331].

Erectile dysfunction is also frequently associated with other urological conditions and procedures (Table 7). Epidemiological studies have demonstrated consistent evidence for an association between LUTS/BPH and sexual dysfunction, regardless of age, other co-morbidity and lifestyle factors [332]. The Multinational Survey on the Aging Male study, performed in the USA, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, and the UK, systematically investigated the relationship between LUTS and sexual dysfunction in > 12,000 men aged 50-80 years. In the 83% of men who were reported to be sexually active, the overall prevalence of LUTS was 90%, with an overall 49% prevalence of ED and a reported complete absence of erections in 10% of patients. The overall prevalence of ejaculatory disorders was 46% [333]. Regardless of the employed technique, surgery for BPH-LUTS had no significant impact on erectile function at long-term (5-year) follow-up, while a slight advantage is demonstrated for prostate urethral lift (PUL) over conventional TURP at 24 months follow-up [334]. A post-operative improvement of erectile function was even found depending on the degree of LUTS improvement [335,336]. An association has been confirmed between ED and CP/CPPS [336], and bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis (BPS/IC), mostly in younger men [337]. An association between ED and PE has also been demonstrated (see Section 6.2) [338]. Recent evidence showed that ED is a mild, short-term and transient complication of prostate biopsy, regardless of the trans-rectal or trans-perineal approach employed [339].

An increased risk of ED is reported following [340] open urethroplasty, especially for correction of posterior strictures [341], with recent findings emphasising the importance of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in urethral reconstructive surgery to better report actual sexual function outcomes [342,343].

Table 7: Urological conditions associated with ED

Urological Condition | Association with ED |

LUTS/BPH [332] | Depending on the severity of LUTS and patients’ age/population characteristics: Odds ratio (OR) of ED among men with LUTS/BPH ranges from 1.52 to 28.7 and prevalence ranges from 58% to 80% |

Surgery for BPH/LUTS (TURP, laser, open, laparoscopic, etc.) [335] | Overall, absence of significant variations in terms of erectile function scores after surgery |

Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome [336] | Prevalence of ED among patients with CP/CPPS 29% [24%-33%, 95%CI], Range: 11% - 56% among studies |

Bladder Pain Syndrome/Interstitial Cystitis [337] | OR of BPS/IC among patients with ED. Overall: OR (adjusted) = 1.75 [1.12 – 2.71, 95% CI] Age > 60: OR (adjusted) = 1.07 [0.41 – 2.81, 95% CI] Age 40-59: OR (adjusted) = 1.44 [1.02 – 2.12, 95% CI] Age 18-39: OR (adjusted) = 10.40 [2.93 – 36.94, 95% CI] |

Premature Ejaculation [340] | OR of ED among patients with PE = 3.68 [2.61 – 5.68, 95% CI] |

Urethroplasty surgery for posterior urethral strictures [341] | OR of ED after posterior urethroplasty = 2.51 [1.82 – 3.45, 95% CI] |

CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; TURP = transurethral resection of the prostate; ED = erectiledysfunction; BPS/IC = bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis; LUTS = lower urinary tract symptoms; PE = premature ejaculation.

Several studies have shown that lifestyle modification [344], including physical activity [345], weight loss [346] and pharmacotherapy [294,347,348] for CVD risk factors may be of help in improving sexual function in men with ED. Meta-analytic data reveals a positive effect of lipid-lowering therapy with statins on erectile function [349,350]. However, it should be emphasised that further controlled prospective studies are necessary to determine the effects of exercise or other lifestyle changes in the prevention and treatment of ED [344].

5.3. Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of ED may be vasculogenic, neurogenic, anatomical, hormonal, drug-induced and/or psychogenic (Table 8) [272]. In most cases, numerous pathophysiological pathways can co-exist and may all negatively impact on erectile function.

The proposed ED etiological and pathophysiological division should not be considered prescriptive. In most cases, ED is associated with more than one pathophysiological factor and very often, if not always, will have a psychological component. Likewise, organic components can negatively affect erectile function with different pathophysiological effects. Therefore, Table 8 must be considered for diagnostic classifications only (along with associated risk factors for each subcategory).

Table 8: Pathophysiology of erectile dysfunction

Vasculogenic |

Recreational habits (i.e., cigarette smoking) |

Lack of regular physical exercise |

Obesity |

Cardiovascular diseases (e.g., hypertension, coronary artery disease, peripheral vasculopathy) |

Type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus; hyperlipidaemia; metabolic syndrome; hyperhomocysteinemia |

Major pelvic surgery (e.g., radical prostatectomy) or radiotherapy (pelvis or retroperitoneum) |

Neurogenic |

Central causes |

Degenerative disorders (e.g., multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, multiple atrophy, etc.) |

Spinal cord trauma or diseases |

Stroke |

Central nervous system tumours |

Peripheral causes |

Type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus |

Chronic renal failure, chronic liver failure |

Polyneuropathy |

Surgery (major surgery of pelvis/retroperitoneum) or radiotherapy (pelvis or retroperitoneum) |

Surgery of the urethra (urethral stricture, open urethroplasty, etc.) |

Anatomical or structural |

Hypospadias, epispadias; micropenis |

Phimosis |

Peyronie’s disease |

Penile cancer (other tumours of the external genitalia) |

Hormonal |

Diabetes mellitus; Metabolic Syndrome; |

Hypogonadism (any type) |

Hyperthyroidism |

Hyper- and hypocortisolism (Cushing’s disease, etc.) |

Panhypopituitarism and multiple endocrine disorders |

Mixed pathophysiological pathways |

Chronic systemic diseases (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disorders, hyperhomocysteinemia, hyperuricemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, rheumatic disease) |

Psoriasis, gouty arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, chronic periodontitis, open-angle glaucoma, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic fatigue syndrome, allergic rhinitis, obstructive sleep apnoea, depression |

Iatrogenic causes (e.g. TRUS-guided prostate biopsy) |

Drug-induced |

Antihypertensives (i.e., thiazidediuretics, beta-blockers)* |

Antidepressants (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclics) |

Antipsychotics |

Antiandrogens (GnRH analogues and antagonists; 5-ARIs) |

Recreational drugs (e.g., heroin, cocaine, marijuana, methadone, synthetic drugs, anabolic steroids, excessive alcohol intake) |

Psychogenic |

Generalised type (e.g., lack of arousability and disorders of sexual intimacy) |

Situational type (e.g., partner-related, performance-related issues or due to distress) |

Trauma |

Penile fracture |

Pelvic fractures |

GnRH = gonadotropin-releasing hormone; 5-ARIs = 5α-reductase inhibitors.

*A symmetry analysis showed that cardiovascular drugs do not strongly affect the risk of subsequently being prescribed as anti-erectogenic drug. The analysis only assessed the short-term risk .351

5.3.1. Pelvic surgery and prostate cancer treatment

Pelvic surgery, especially for oncological disease (e.g., radical prostatectomy (RP) [352] or radical cystectomy [353] and colorectal surgery [354]), may have a negative impact on erectile function and overall sexual health. The most relevant causal factor is a lesion occurring in the neurovascular bundles that control the complex mechanism of the cavernous erectile response, whose preservation (either partial or complete) during surgery eventually configures the so-called nerve-sparing (NS) approach [355]. Therefore, surgery resulting in damage of the neurovascular bundles, may result in ED, although NS approaches have been adopted over the last few decades. This approach is applicable to all types of surgery that are potentially harmful to erectile function, although to date, only the surgical treatment of PCa has enough scientific evidence supporting its potential pathophysiological association with ED [356,357]. However, even non-surgical treatments of PCa (i.e., radiotherapy, or brachytherapy) can be associated with ED [358,359]. The concept of active surveillance for the treatment of PCa was developed to avoid over-treatment of non-significant localised low-risk diseases, while limiting potential functional adverse effects (including ED). However, it is interesting that data suggest that even active surveillance has a detrimental impact on erectile function (and sexual well-being as a whole) [360-362].

To date, some of the most robust data on PROMs including erectile function, comparing treatments for clinically localised PCa come from the Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) trial, in which 1,643 patients were randomised to active treatment (either RP or RT) and active monitoring and were followed-up for 6 years [363]. Sexual function, including erectile function, and the effect of sexual function on QoL were assessed with the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite with 26 items (EPIC-26) instrument [364,365]. At baseline, 67% of men reported erections firm enough for sexual intercourse but this fell to 52% in the active monitoring group, 22% in the RT group, and 12% in the RP group, at 6-months’ assessment. The worst trend over time was recorded in the RP group (with 21% erections firm enough for intercourse after 3 years vs. 17% after 6 years, respectively). In the RT group, the percentage of men reporting erections firm enough for intercourse increased between 6 and 12 months, with a subsequent decrease to 27% at 6-years assessment. The percentage declined over time on a yearly basis in the active monitoring group, with 41% of men reporting erections firm enough for intercourse at 3 years and 30% at 6 years [363].

Radical prostatectomy (open, laparoscopic or robot-assisted) is a widely performed procedure with a curative intent for patients presenting with clinically localised intermediate- or high-risk PCa and a life expectancy of > 10 years based on health status and co-morbidity [366]. This procedure may lead to treatment-specific sequelae affecting health-related QoL. Men undergoing RP (any technique) should be adequately informed before the operation that there is a significant risk of sexual changes other than ED, including decreased libido, changes in orgasm, anejaculation, Peyronie’s-like disease, and changes in penile length [357,359]. These outcomes have become increasingly important with the more frequent diagnosis of PCa in both younger and older men [367,368]. Research has shown that 25-75% of men experience post-RP ED [369], even though these findings had methodological flaws; in particular, the heterogeneity of reporting and assessment of ED among the studies [356,370]. Conversely, the rate of unassisted post-operative erectile function recovery ranged between 20-25% in most studies. These rates have not substantially improved or changed over the past 17 years, despite growing attention to post-surgical rehabilitation protocols and refinement of surgical techniques [370-372].

Overall, patient age, baseline erectile function and surgical volume, with the consequent ability to preserve the neurovascular bundles, seem to be the main factors in promoting the highest rates of post-operative EF [357,367,369,373]. Regardless of the surgical technique, surgeons’ experience may clearly impact on post-operative EF outcome; in particular when surgeons have a caseload greater than 25 RP cases per year or total cumulative experience of >1,000 RP cases results in better EF outcomes after RP [374]. Patients being considered for nerve-sparing RP (NSRP) should ideally be potent pre-operatively [367]. The recovery time following surgery is of clinical importance in terms of post-operative recovery of EF. Available data confirm that post-operative EF recovery can occur up to 48 months after RP [375]. Likewise, it has been suggested that post-operative therapy (any type) should be commenced as soon as possible after the surgical procedure [367,369], although evidence suggests that the number of patients reporting return of spontaneous EF has not increased.

In terms of the effects of surgical interventions (e.g., robot-assisted RP [RARP] vs. other types of surgery), data are still conflicting. An early systematic review showed a significant advantage in favour of RARP in comparison with open retropubic RP in terms of 12-month potency rates [376], without significant differences between laparoscopic RP and RARP. Some recent reports confirmed that the probability of EF recovery is about twice as high for RARP compared with open RP [377]. More recently, a prospective, controlled, non-randomised trial of patients undergoing RP in 14 Swedish centres comparing RARP versus open retropubic RP, showed a small improvement in EF after RARP [378]. Conversely, a randomised controlled phase 3 study of men assigned to open RP or RARP showed that the two techniques yielded similar functional outcomes at 12 weeks [379]. More controlled prospective well-designed studies, with longer follow-up, are necessary to determine if RARP is superior to open RP in terms of post-operative ED rates [380]. To overcome the problem of heterogeneity in the assessment of EF, for which there is variability in terms of the PROMs used (e.g., International Index of Erectile Function [IIEF], IIEF-5, Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite with 26 items [EPIC 26], Sexual Health Inventory for Men, etc.) to measure potency or EF, the criteria used to define restoration of EF should be re-evaluated utilising objective and validated thresholds (e.g., normalisation of scores or return to baseline EF) [356].

Erectile dysfunction is also a common problem after both external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) and brachytherapy for PCa. A systematic review and meta-analysis including men treated with EBRT (65%), brachytherapy (31%) or both (4%) showed that the post-treatment prevalence of ED was 34% at 1 year and 57% at 5.5 years, respectively [381,382]. Similar findings have been reported for stereotactic radiotherapy with 26-55% of previously sexually functioning patients reporting ED at 5 years [383].

Recently other modalities have emerged as potential therapeutic options in patients with clinically-localised PCa, including whole gland and focal (lesion-targeted) treatments, to ablate tumours selectively while limiting sexual toxicity by sparing the neurovascular bundles. These include high-intensity focused US (HIFU), cryo-therapeutic ablation of the prostate (cryotherapy), focal padeliporfin-based vascular-targeted photodynamic therapy and focal RT by brachytherapy or CyberKnife®. All these approaches have been reported to have a less-negative impact on EF with many studies reporting a complete recovery at one-year follow-up [384]. However, prospective RCTs are needed to compare the functional and oncological outcomes using different treatment modalities [385,386].

5.3.2. Summary of evidence on the epidemiology/aetiology/pathophysiology of ED

Summary of evidence | LE |

Erectile dysfunction is common worldwide. | 2b |

Erectile dysfunction shares common risk factors with cardiovascular disease. | 2b |

Lifestyle modification (regular exercise and decrease in BMI) can improve erectile function. | 1b |

Erectile dysfunction is a symptom, not a disease. Some patients may not be properly evaluated or receive treatment for an underlying disease or condition that may be causing ED. | 4 |

Erectile dysfunction is common after RP, irrespective of the surgical technique used. | 2b |

Erectile dysfunction is common after external radiotherapy and brachytherapy. | 2b |

Erectile dysfunction is less common after cryotherapy and high-intensity focused US. | 2b |

5.4. Diagnostic evaluation (basic work-up)

5.4.1. Medical and sexual history

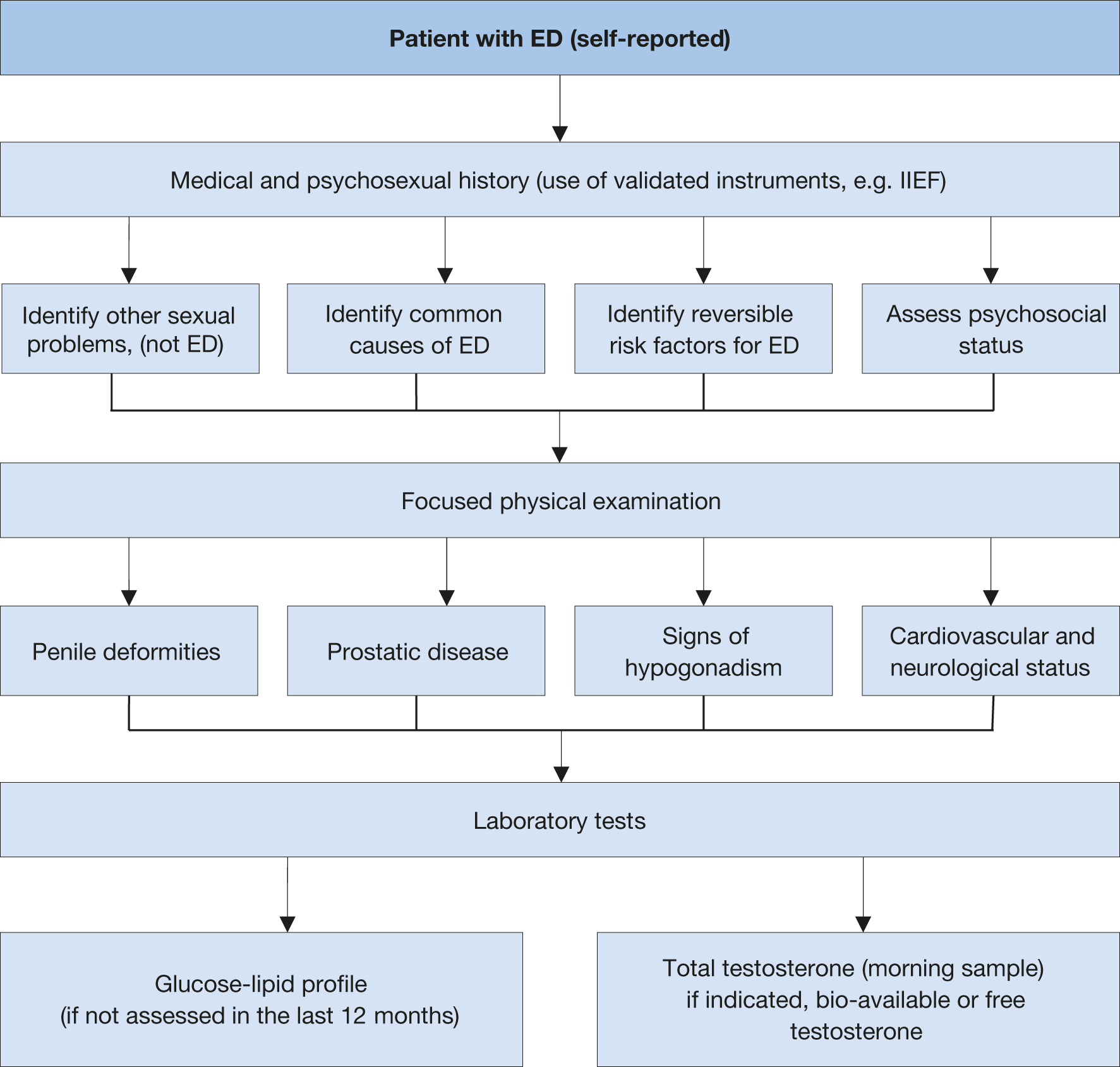

The first step in evaluating ED is always a detailed medical and sexual history of patients and, when available, their partners [387]. It is important to establish a relaxed atmosphere during history-taking. This will make it easier to ask questions about erectile function and other aspects of the patient’s sexual history; and to explain the diagnosis and therapeutic approach to the patient and their partner. Figure 3 lists the minimal diagnostic evaluation (basic work-up) in patients with ED.

The sexual history must include information about previous and current sexual relationships, current emotional status, onset and duration of the erectile problem, and previous consultations and treatments. The sexual health status of the partner(s) (when available) can also be useful. A detailed description should be made of the rigidity and duration of both sexually-stimulated and morning erections and of problems with sexual desire, arousal, ejaculation, and orgasm [388,389]. Validated psychometric questionnaires, such as the IIEF [111] or its short version (i.e., Sexual Health Inventory for Men; SHIM) [390], help to assess the different sexual function domains (i.e. sexual desire, EF, orgasmic function, intercourse satisfaction, and overall satisfaction), as well as the potential impact of a specific treatment modality. Similarly, structured interviews allow the identification and quantification of the different underlying factors affecting erectile function [391].

Psychometric analyses also support the use of the Erectile Hardness Score (EHS) for the assessment of penile rigidity in practice and in clinical trials research [392]. In cases of depressive mood, clinicians may use the Beck Depressive Inventory [393], which is one of the most recognised self-reported measures in the field, takes approximately 10 minutes to complete, and assigns the patient to a specific level of depression (varying from “normal mood” to “extreme depression”).

Patients should always be screened for symptoms of possible hypogonadism, including decreased energy and libido, and fatigue; potential cognitive impairment may be also observed in association with hypogonadism (see Sections 3.5 and 3.6), as well as for LUTS. In this regard, although LUTS/BPH in themselves do not represent contraindications to treatment for LOH, screening for LUTS severity is clinically relevant [394].

5.4.2. Physical examination

Every patient must be given a physical examination focused on the genitourinary, endocrine, vascular and neurological systems [395,396]. A physical examination may reveal unsuspected diagnoses, such as Peyronie’s disease, pre-malignant or malignant genital lesions, prostatic enlargement or irregularity/nodularity, or signs and symptoms suggestive of hypogonadism (e.g., small testes or alterations in secondary sexual characteristics).

Assessment of previous or concomitant penile abnormalities (e.g., hypospadias, congenital curvature, or Peyronie’s disease with preserved rigidity) during the medical history and the physical examination is mandatory.

Blood pressure and heart rate should be measured if they have not been assessed in the previous 3-6 months. Likewise, either BMI calculation or waist circumference measurement should be undertaken to assess patients for comorbid conditions (e.g., MetS).

5.4.3. Laboratory testing

Laboratory testing must be tailored to the patient’s complaints and risk factors. Patients should undergo a fasting blood glucose or HbA1c and lipid profile measurement if they have not been assessed in the previous 12 months. Hormonal tests should include early morning total testosterone in a fasting state. The bio-available or calculated-free testosterone values may sometimes be needed to corroborate total testosterone measurements (see sections 3.2.1 and 3.5.1). However, the threshold of testosterone required to maintain an erection is low and ED is usually a symptom of more severe cases of hypogonadism (see Sections 3.5 and 3.6) [51,55,397-399]. Additional laboratory tests may be considered in selected patients with specific signs and associated symptoms (e.g., total PSA) [400], PRL and LH [401]). Although physical examination and laboratory evaluation of most men with ED may not reveal the exact diagnosis, clinical and biochemical evaluation presents an opportunity to identify comorbid conditions [396].

Figure 3: Minimal diagnostic evaluation (basic work-up) in patients with ED ED = erectile dysfunction; IIEF = International Index of Erectile Function.

ED = erectile dysfunction; IIEF = International Index of Erectile Function.

5.4.4. Cardiovascular system and sexual activity: the patient at risk

Patients who seek treatment for sexual dysfunction have a high prevalence of CVDs. Epidemiological surveys have emphasised the association between cardiovascular/metabolic risk factors and sexual dysfunction in both men and women [402]. Overall, ED can improve the sensitivity of screening for asymptomatic CVD in men with diabetes [403,404]. Erectile dysfunction significantly increases the risk of CVD, coronary heart disease and stroke. Furthermore, the results of a recent prospective cohort study showed that ED is an independent predictor for incident atrial fibrillation [405]. All of these causes of mortality and the increases are probably independent of conventional cardiovascular risk factors [278,279,406,407]. Longitudinal data from an observational population-based study of 965 men without CVD showed that younger men (especially those < 50 years) with transient and persistent ED have an increased Framingham CVD risk [408]. Moreover, a prospective cohort study assessing the potential link between cardiovascular risk factors, ED (as defined with the IIEF questionnaire) and exercise stress test (EST) confirmed that ED patients with a positive EST should be regarded as extremely high risk for cardiovascular events, to the point that all male patients referred for EST should be screened for ED [409].

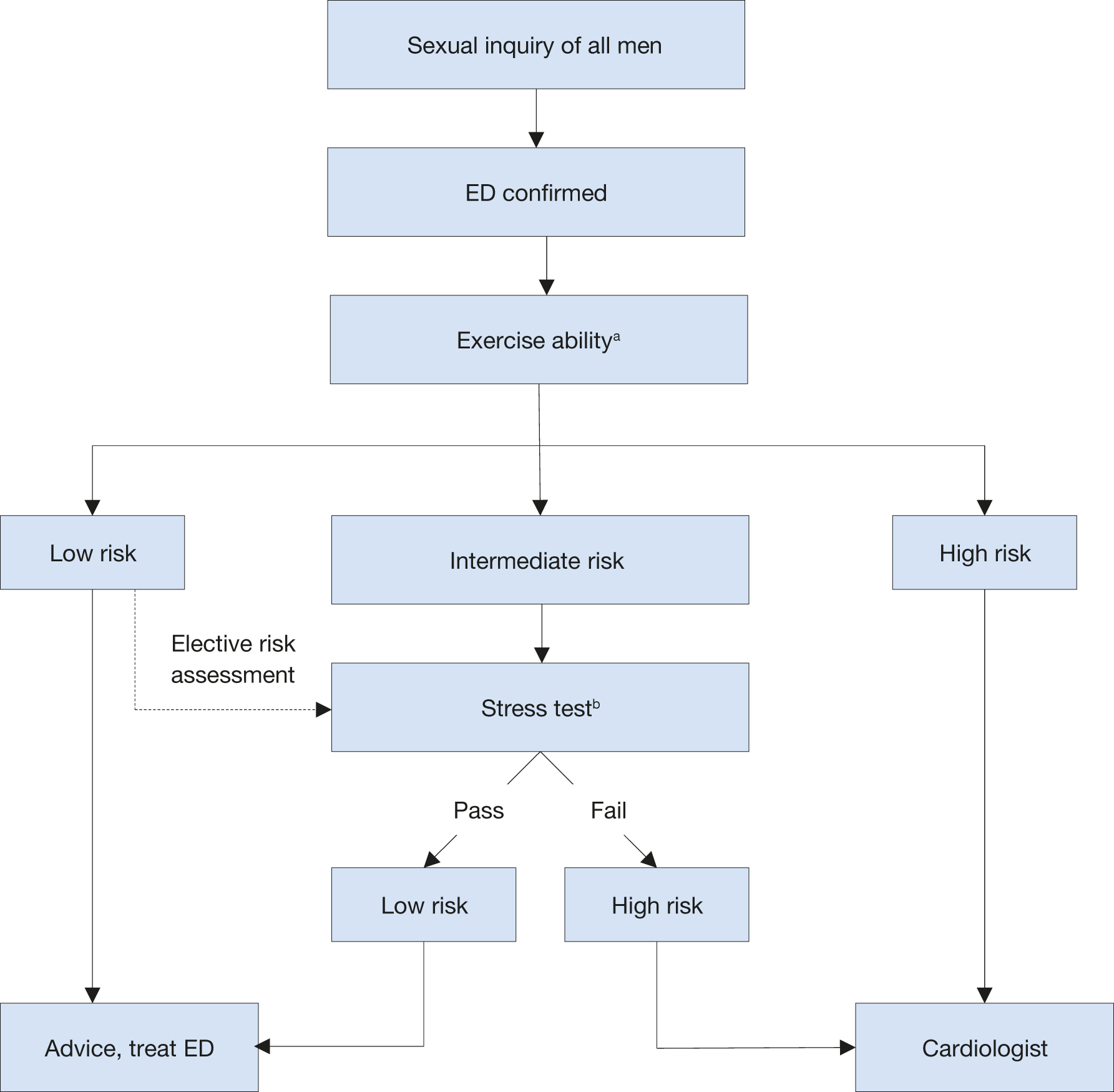

The current EAU Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of men with ED have been adapted from previously published recommendations from the Princeton Consensus conferences on sexual dysfunction and cardiac risk [410]. The Princeton Consensus (Expert Panel) Conference is dedicated to optimising sexual function and preserving cardiovascular health [410-412]. Accordingly, patients with ED can be stratified into three cardiovascular risk categories (Table 9), which can be used as the basis for a treatment algorithm for initiating or resuming sexual activity (Figure 3). It is also possible for the clinician to estimate the risk of sexual activity in most patients from their level of exercise tolerance, which can be determined when taking the patient’s history [348].

Table 9: Cardiac risk stratification (based on 2nd and 3rd Princeton Consensus)

Low-risk category | Intermediate-risk category | High-risk category |

Asymptomatic, < 3 risk factors for CAD (excluding sex) | > 3 risk factors for CAD (excluding sex) | High-risk arrhythmias |

Mild, stable angina (evaluated and/or being treated) | Moderate, stable angina | Unstable or refractory angina |

Uncomplicated previous MI | Recent MI (> 2, < 6 weeks) | Recent MI (< 2 weeks) |

LVD/CHF (NYHA class I or II) | LVD/CHF (NYHA class III) | LVD/CHF (NYHA class IV) |

Post-successful coronary revascularisation | Non-cardiac sequelae of atherosclerotic disease (e.g., stroke, peripheral vascular disease) | Hypertrophic obstructive and other cardiomyopathies |

Controlled hypertension | Uncontrolled hypertension | |

Mild valvular disease | Moderate-to-severe valvular disease |

CAD = coronary artery disease; CHF = congestive heart failure; LVD = left ventricular dysfunction;MI = myocardial infarction; NYHA = New York Heart Association.

Figure 4: Treatment algorithm for determining level of sexual activity according to cardiac risk in ED(based on 3rd Princeton Consensus)  a Sexual activity is equivalent to walking 1 mile on the flat in 20 minutes or briskly climbing two flights of stairs in 10 seconds.

a Sexual activity is equivalent to walking 1 mile on the flat in 20 minutes or briskly climbing two flights of stairs in 10 seconds.

b Sexual activity is equivalent to 4 minutes of the Bruce treadmill protocol.

5.4.4.1. Low-risk category

The low-risk category includes patients who do not have any significant cardiac risk associated with sexual activity. Low-risk is typically implied by the ability to perform exercise of modest intensity, which is defined as, > 6 metabolic equivalents of energy expenditure in the resting state, without symptoms. According to current knowledge of the exercise demand or emotional stress associated with sexual activity, low-risk patients do not need cardiac testing or evaluation before initiation or resumption of sexual activity or therapy for sexual dysfunction.

5.4.4.2. Intermediate- or indeterminate-risk category

The intermediate- or indeterminate-risk category consists of patients with an uncertain cardiac condition or patients whose risk profile requires testing or evaluation before the resumption of sexual activity. Based upon the results of testing, these patients may be moved to either the high- or low-risk group. A cardiology consultation may be needed in some patients to help the primary physician determine the safety of sexual activity.

5.4.4.3. High-risk category

High-risk patients have a cardiac condition that is sufficiently severe and/or unstable for sexual activity to carry a significant risk. Most high-risk patients have moderate-to-severe symptomatic heart disease. High-risk individuals should be referred for cardiac assessment and treatment. Sexual activity should be stopped until the patient’s cardiac condition has been stabilised by treatment, or a decision made by the cardiologist and/or internist that it is safe to resume sexual activity.

5.5. Diagnostic Evaluation (advanced work-up)

Most patients with ED can be managed based on their medical and sexual history; conversely, some patients may need specific diagnostic tests (Tables 10 and 11).

5.5.1. Nocturnal penile tumescence and rigidity test

The nocturnal penile tumescence and rigidity (NPTR) test applies nocturnal monitoring devices that measure the number of erectile episodes, tumescence (circumference change by strain gauges), maximal penile rigidity, and duration of nocturnal erections. The NPTR assessment should be performed on at least two separate nights. A functional erectile mechanism is indicated by an erectile event of at least 60% rigidity recorded on the tip of the penis that lasts for > 10 minutes [413]. Nocturnal penile tumescence and rigidity monitoring is an attractive approach for objectively differentiating between organic and psychogenic ED (patients with psychogenic ED usually have normal findings in the NPTR test). However, many potential confounding factors (e.g., situational) may limit its routine use for diagnostic purposes [414].

5.5.2. Intracavernous injection test

The intracavernous injection test gives limited information about vascular status. A positive test is a rigid erectile response (unable to bend the penis) that appears within 10 minutes after the intracavernous injection and lasts for 30 minutes [415]. Overall, the test is inconclusive as a diagnostic procedure and a duplex Doppler study of the penis should be requested, if clinically warranted.

5.5.3. Dynamic duplex ultrasound of the penis

Dynamic duplex ultrasound (US) of the penis is a second-level diagnostic test that specifically studies the haemodynamic pathophysiology of erectile function. Therefore, in clinical practice, it is usually applied in those conditions in which a potential vasculogenic aetiology of ED (e.g., diabetes mellitus, renal transplantation, multiple concomitant CV risk factors and/or overt peripheral vascular disease, and poor responders to oral therapy) is suspected. Peak systolic blood flow > 30 cm/s, end-diastolic velocity < 3 cm/s and resistance index > 0.8 are considered normal [416,417]. Recent data suggest that duplex scanning as a haemodynamic study may be better at tailoring therapy for ED, such as for low-intensity shock wave treatment (LI-SWT) in men with vasculogenic ED [418]. Further vascular investigation is unnecessary if a duplex US examination is normal.

5.5.4. Arteriography and dynamic infusion cavernosometry or cavernosography

Pudendal arteriography should be performed only in patients who are being considered for penile revascularisation [419]. Recent studies have advocated the use of computed tomography (CT) angiography as a diagnostic procedure prior to penile artery angioplasty for patients with ED and isolated penile artery stenosis [420]. Nowadays, dynamic infusion cavernosometry or cavernosography are infrequently used tools for diagnosing venogenic ED.

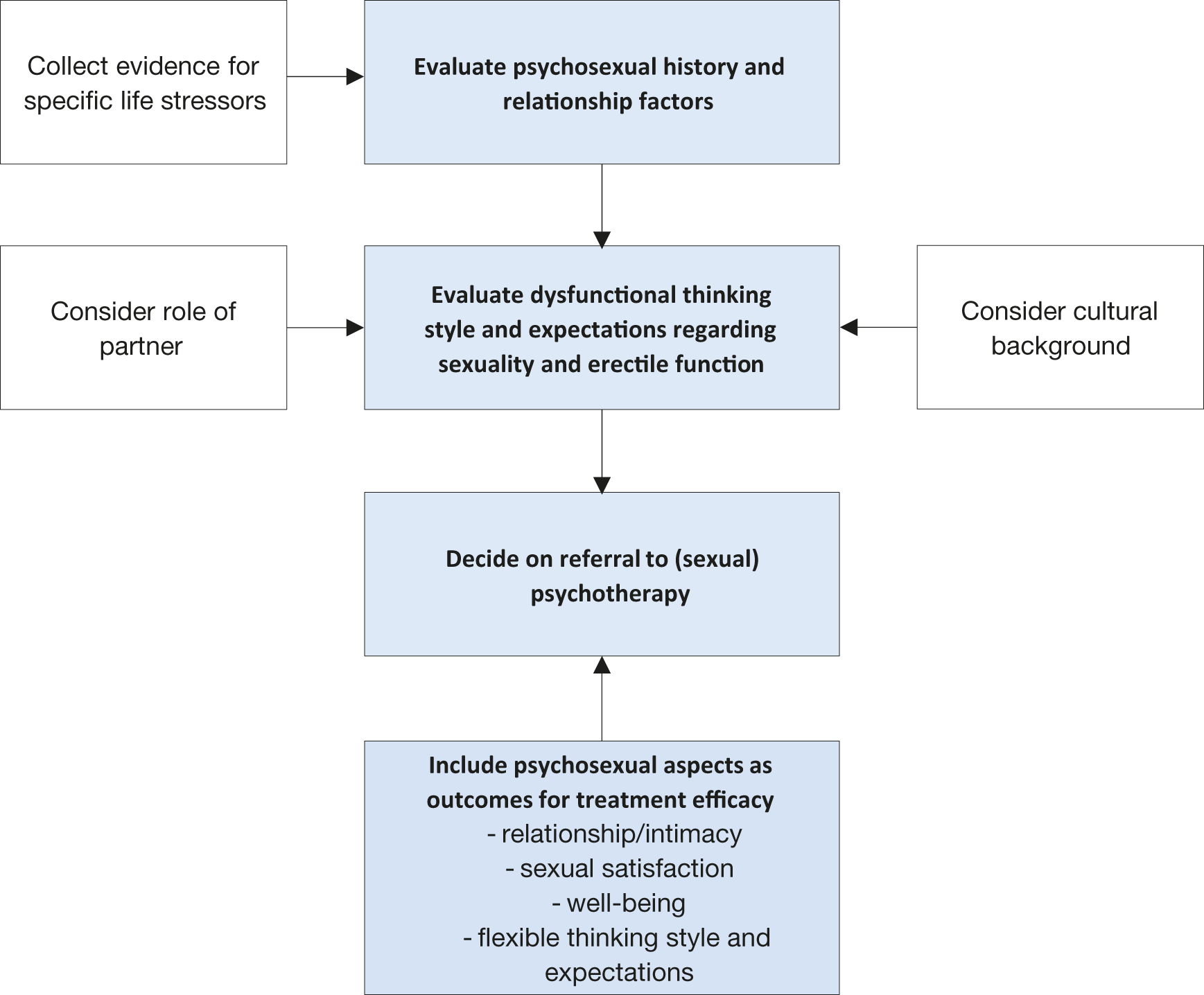

5.5.5. Psychopathological and psychosocial assessment

Mental health issues and psychological distress are frequently comorbid with ED [421]. This is most evident for depression and anxiety related disorders, but may also include transitory states of altered mood (i.e., dysfunctional affective states resulting from a specific life stressor or crisis) [301,422,423]. Relationship factors, including lack of satisfaction with the partner, poor sexual relationships, length of the relationship, or feeling emotionally disconnected from the partner during sex, have been related to erectile difficulties and dysfunction [422,424,425]. In contrast, intimacy was found to be a protective factor in ED [291,426]. Additionally, the cognitive factors underpinning organic and non-organic ED must also be assessed. Cognitive factors include male dysfunctional thinking styles and expectations about sexuality and sexual performance. These expectations result from the sexuality norms and stereotypes, shared by a given culture. Expectations emphasising high sexual performance in men, result in anxiety, which acts as a maintenance factor for ED [427,428]. Unrealistic expectations about male sexual performance may further align with internal causal attributions regarding the loss of erection (i.e., men attribute the loss of erection to themselves [sense of personal inadequacy]), thereby worsening ED [427,429]. Likewise, poor self-esteem and cognitive distraction from erotic cues, are expected to negatively affect ED [430,431].

Psychosexual assessment in ED cases include a clinical interview considering all the previous topics. Clinicians are expected to collect information on the individual’s psychopathological symptoms, life stressors, relationship dynamics, cognitive style, and cognitive distraction sources [430]. Also, self-reported measures are frequently used within the psychosocial context. These may include measurement scales such as the Brief Symptom Inventory [432] for measuring psychopathology symptoms, the Sexual Dysfunctional Beliefs Questionnaire [433] or the Sexual Modes Questionnaire [434] for measuring dysfunctional cognitive styles in men. It is worth noting that most literature follows a heteronormativity view. There is recent evidence suggesting that men who have sex with men (MSM) present specific psychological risks associated with erectile capability regarding anal sex; minority stress, i.e., stress steaming from conflicting sexual identity, was associated with increased erectile difficulties in these men [435]. Therefore, professionals must tailor their assessment in the context of sexual minorities.

Figure 5: Psychopatholgical and psychosocial assessment

Table 10: Indications for specific diagnostic tests for ED

Indications for specific diagnostic tests for ED |

Primary ED (not caused by acquired organic disease or psychogenic disorder). |

Young patients with a history of pelvic or perineal trauma, who could benefit from potentially curative revascularisation surgery or angioplasty. |

Patients with penile deformities that might require surgical correction (e.g., Peyronie’s disease and congenital penile curvature). |

Patients with complex psychiatric or psychosexual disorders. |

Patients with complex endocrine disorders. |

Specific tests may be indicated at the request of the patient or their partner. |

Medico-legal reasons (e.g., implantation of penile prosthesis to document end-stage ED, and sexual abuse). |

Table 11: Specific diagnostic tests for ED

Nocturnal Penile Tumescence and Rigidity (NTPR) using Rigiscan® |

Vascular studies - Intracavernous vasoactive drug injection - Penile dynamic duplex ultrasonography - Penile dynamic infusion cavernosometry and cavernosography - Internal pudendal arteriography |

Specialised endocrinological studies |

Specialised psycho-diagnostic evaluation |

5.5.6. Recommendations for diagnostic evaluation of ED

Recommendations | Strength rating |

Take a comprehensive medical and sexual history in every patient presenting with erectile dysfunction (ED). Consider psychosexual development, including life stressors, cultural aspects, and cognitive/thinking style of the patient regarding their sexual performance. | Strong |

Use a validated questionnaire related to ED to assess all sexual function domains (e.g., International Index of Erectile Function) and the effect of a specific treatment modality. | Strong |

Include a focused physical examination in the initial assessment of men with ED to identify underlying medical conditions and comorbid genital disorders that may be associated with ED. | Strong |

Assess routine laboratory tests, including glucose and lipid profile and total testosterone, to identify and treat any reversible risk factors and lifestyle factors that can be modified. | Strong |

Include specific diagnostic tests in the initial evaluation of ED in the presence of the conditions presented in Table 9. | Strong |

5.6. Treatment of erectile dysfunction

5.6.1. Patient education - consultation and referrals

Educational intervention is often the first approach to sexual complaints, and consists of informing patients about the psychological and physiological processes involved in the individual’s sexual response, in ways the patient can understand. This first level approach has been shown to favour sexual satisfaction in men with ED [436]. Accordingly, consultation with the patient should include a discussion of the expectations and needs of the patient’s and their sexual partner. It should also review the patient’s and partner’s understanding of ED and the results of diagnostic tests, and provide a rationale for treatment selection [437]. Patient and partner education is an essential part of ED management work-up [437,438], and may prevent misleading information that can be at the core of dysfunctional psychological processes underpinning ED.

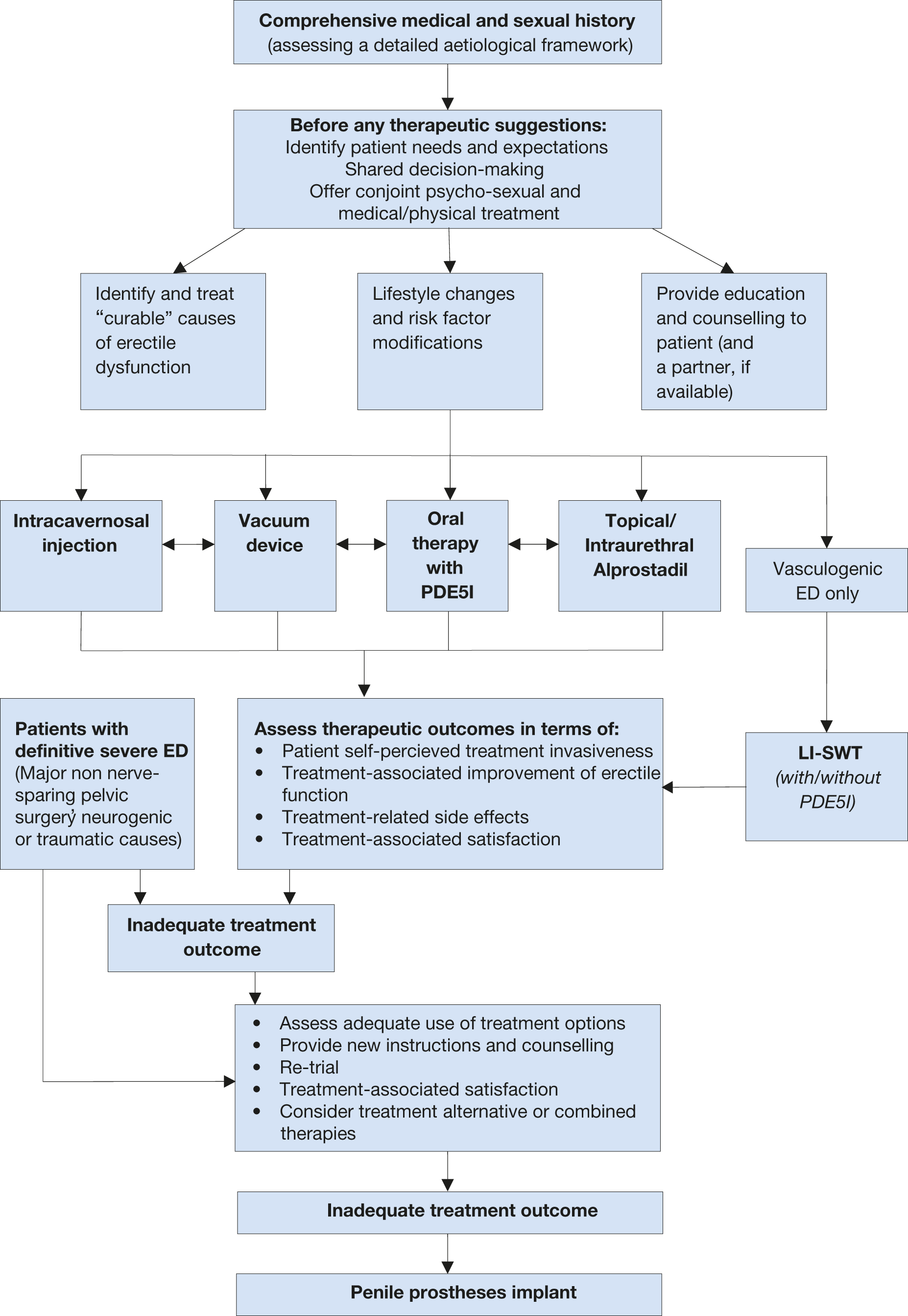

5.6.2. Treatment options

Based on the currently available evidence and the consensus of the Panel, a novel comprehensive therapeutic and decision-making algorithm (Figure 6) for treating ED, which takes into account the level of invasiveness of each therapy and its efficacy, has been developed. This new treatment algorithm was extensively discussed within the Guidelines Panel as an alternative to the traditional three-tier concept, to better tailor a personalised therapy to individual patients, according to invasiveness, tolerability and effectiveness of the different therapeutic options and patients’ expectations. In this context, patients should be fully counselled with respect to all available treatment modalities.

Erectile dysfunction may be associated with modifiable or reversible risk factors, including lifestyle or drug-related factors [344]. These factors may be modified either before, or at the same time as, specific therapies are used. Likewise, ED may be associated with concomitant and underlying conditions (e.g., endocrine disorders and metabolic disorders such as diabetes, and some cardiovascular problems such as hypertension) which should always be well-controlled as the first step of any ED treatment [439]. Major clinical potential benefits of lifestyle changes may be achieved in men with specific co-morbid CV or metabolic disorders, such as diabetes or hypertension [344,440].

As a rule, ED can be treated successfully with current treatment options, but it cannot be cured. The only exceptions are psychogenic ED, post-traumatic arteriogenic ED in young patients, and hormonal causes (e.g., hypogonadism) [55,401], which potentially can be cured with specific treatments. Most men with ED are not treated with cause-specific therapeutic options. This results in a tailored treatment strategy that depends on invasiveness, efficacy, safety and costs, as well as patient preference [437]. In this context, physician-patient (partner, if available) dialogue is essential throughout the management of ED. Interesting insights come from a systematic review that showed a consistent discontinuation rate for all available treatment options (4.4-76% for PDE5Is; 18.6-79.9% for intracavernous injections; 32-69.2% for urethral suppositories; and 30% for penile prostheses). Men’s beliefs about ED treatment, therapeutic ineffectiveness, adverse effects, quality of men’s intimate relationships and treatment costs are the most prevalent barriers to treatment actual use [441].

Figure 6: Management algorithm for erectile dysfunction ED = erectile dysfunction; PDE5Is = phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors; LI-SWT = low-intensity shockwave therapy.

ED = erectile dysfunction; PDE5Is = phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors; LI-SWT = low-intensity shockwave therapy.

5.6.2.1. Oral pharmacotherapy

Four potent selective PDE5Is have been approved by the EMA for treatment of ED [442]. Phosphodiesterase type 5 catalyses the hydrolysis of the second messenger cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) in the cavernous tissue; cGMP is involved in intra-cellular signalling pathways of cavernous smooth muscle. Accumulation of cGMP sets in motion a cascade of events at the intracellular level, which induces a loss of contractile tone of the penile vessels by lowering cytosolic Ca2+. Nitric oxide (NO) has an essential role in promoting the formation of cGMP and other pathways leading to corporeal smooth muscle relaxation and erection of the penis [439,443]. This is associated with increased arterial blood flow, eventually leading to compression of the sub-tunical venous plexus followed by erection [444]. Since they are not initiators of erection, PDE5Is require sexual stimulation to facilitate an erection. Efficacy is defined as an erection, with rigidity, sufficient for satisfactory intercourse [439].

Sildenafil

Sildenafil was launched in 1998 and was the first PDE5I available on the market [445]. It is administered in doses of 25, 50 and 100 mg. The recommended starting dose is 50 mg and should be adapted according to the patient’s response and adverse effects [445]. Sildenafil is effective 30-60 minutes after administration [445]. Its efficacy is reduced after a heavy, fatty meal due to delayed absorption. Efficacy may be maintained for up to 12 hours [446]. The pharmacokinetic profile for sildenafil is presented in Table 12. Adverse events (Table 13) are generally mild in nature and self-limited [447,448]. After 24 weeks in a dose-response study, improved erections were reported by 56%, 77% and 84% in a general ED population taking 25, 50 and 100 mg sildenafil, respectively, compared to 25% of men taking placebo [449]. Sildenafil significantly improved patient scores for IIEF, sexual encounter profile question 2 (SEP2), SEP question 3 (SEP3) and General Assessment Questionnaire (GAQ) and treatment satisfaction. The efficacy of sildenafil in almost every subgroup of patients with ED has been successfully established, irrespective of age [450]. Recently, an orally disintegrating tablet (ODT) of sildenafil citrate at a dose of 50 mg has been developed, mainly for patients who have difficulty swallowing solid dosage forms.

Tadalafil

Tadalafil was licensed for treatment of ED in February 2003 and is effective from 30 minutes after administration, with peak efficacy after about 2 hours [451]. Efficacy is maintained for up to 36 hours [451] and is not affected by food [452]. Usually, tadalafil is administered in on-demand doses of 10 and 20 mg or a daily dose of 5 mg. The recommended on-demand starting dose is 10 mg and should be adapted according to the patient’s response and adverse effects [451,453]. Pharmacokinetic data for tadalafil are presented in Table 12. Adverse effects (Table 13) are generally mild in nature and self-limited by continuous use. In pre-marketing studies, after 12 weeks of treatment in a dose-response study, improved erections were reported by 67% and 81% of men with ED taking 10 and 20 mg tadalafil, respectively, compared to 35% of men in the placebo control group [451]. Tadalafil significantly improves patient scores for IIEF, SEP2, SEP3, and GAQ and treatment satisfaction [451].

Efficacy of tadalafil has been confirmed in post-marketing studies [442,454] and in almost every subgroup of patients with ED, including difficult-to-treat subgroups (e.g., diabetes mellitus) [455].

Tadalafil has also been shown to have a net clinical benefit in the short-term on ejaculatory and orgasmic functions in ED patients [456].

Daily tadalafil 5 mg has also been approved and licensed as a monotherapy in men with BPH-related LUTS, due to its ability to significantly improve urinary symptoms [457]. Therefore, its use may be considered in both patients with ED only and in patients also complaining of concomitant LUTS, and wishing to benefit from a single therapy [458]. Data have confirmed that 40% of men aged > 45 years were combined responders for ED and LUTS/BPH to treatment with tadalafil 5 mg once daily, with symptom improvement after 12 weeks [459]. No data beyond 12 months are available in terms of efficacy and tolerability for the use of daily tadalafil 5 mg as a combined therapy for both ED and LUTS.

Vardenafil

Vardenafil became commercially available in March 2003 and is effective from 30 minutes after administration [460], with one of three patients achieving satisfactory erections within 15 minutes of ingestion [461]. Its effect is reduced by a heavy, fatty meal. Doses of 5, 10 and 20 mg have been approved for on-demand treatment of ED. The recommended starting dose is 10 mg and should be adapted according to the patient’s response and adverse effects [462]. Pharmacokinetic data for vardenafil are presented in Table 12. Adverse events (Table 13) are generally mild in nature and self-limited by continuous use [462]. After 12 weeks in a dose-response study, improved erections were reported by 66%, 76% and 80% of men with ED taking 5, 10 and 20 mg vardenafil, respectively, compared with 30% of men taking placebo [462,463]. Vardenafil significantly improved patient scores for IIEF, SEP2, SEP3, and GAQ and treatment satisfaction.

Efficacy has been confirmed in post-marketing studies [462,463]. The efficacy of vardenafil in almost every subgroup of patients with ED, including difficult-to-treat subgroups (e.g., diabetes mellitus), has been successfully established. An orodispersable tablet (ODT) formulation of vardenafil has been released [463]. Overall, ODT formulations offer improved convenience over film-coated formulations and may be preferred by patients. As for ODT, absorption is unrelated to food intake and they exhibit better bio-availability compared to film-coated tablets [464]. The efficacy of vardenafil ODT has been demonstrated in several RCTs and did not seem to differ from the regular formulation [464-466].

Avanafil

Avanafil is a highly-selective PDE5I that became commercially available in 2013 [467]. Avanafil has a high ratio of inhibiting PDE5 as compared with other PDE subtypes, ideally allowing for the drug to be used for ED while minimising adverse effects (although head-to-head comparisons are not yet available) [468]. Doses of 50, 100 and 200 mg have been approved for on-demand treatment of ED [467]. The recommended starting dose is 100 mg taken as needed 15-30 minutes before sexual activity and the dose may be adapted according to efficacy and tolerability [467,469,470]. In the general population with ED, the mean percentage of attempts resulting in successful intercourse was approximately 47%, 58% and 59% for the 50, 100 and 200 mg groups, respectively, as compared with ~28% for placebo [467,469]. Data from sexual attempts made within 15 minutes of treatment showed successful attempts in 64%, 67% and 71% of cases treated with avanafil 50, 100 and 200 mg, respectively. Dose adjustments are not warranted based on renal function, hepatic function, age or sex [469]. Pharmacokinetic data for avanafil are presented in Table 12 [467,469]. Adverse effects are generally mild in nature (Table 13) [467,469]. Pairwise meta-analytic data from available studies have suggested that avanafil significantly improved patient scores for IIEF, SEP2, SEP3 and GAQ, with an evident dose-response relationship [467,471]. Administration with food may delay the onset of effect compared with administration in a fasting state but avanafil can be taken with or without food [472]. The efficacy of avanafil in many groups of patients with ED, including difficult-to-treat subgroups (e.g., diabetes mellitus), has been successfully established. As for dosing, 36.4% (28 of 77) of sexual attempts (SEP3) at < 15 minutes were successful with avanafil vs. 4.5% (2 of 44) after placebo (P < 0.01) [473]. A recent meta-analysis confirmed that avanafil had comparable efficacy with sildenafil, vardenafil and tadalafil [472].

Choice or preference among the different PDE5Is

To date, no data are available from double- or triple-blind multicentre studies comparing the efficacy and/or patient preference for the most-widely available PDE5Is (i.e., sildenafil, tadalafil, vardenafil, and avanafil). Choice of drug depends on frequency of intercourse (occasional use or regular therapy, 3-4 times weekly) and the patient’s personal experience. Patients need to know whether a drug is short- or long-acting, its possible disadvantages, and how to use it. Two different network meta-analyses demonstrated that ED patients who prioritise high efficacy must use sildenafil 50 mg whereas those who optimise tolerability should initially use tadalafil 10 mg and switch to udenafil 100 mg if the treatment is not sufficient (however, udenafil 100 mg is not EMA or FDA approved and is not available in Europe) [454,474]. The results of another clinical trial have revealed that tadalafil 5 mg once daily may improve EF among men who have a partial response to on-demand PDE5I therapy [475].

Continuous use of PDE5Is

From a pathophysiological standpoint, animal studies have shown that chronic use of PDE5Is significantly improves or prevents the intracavernous structural alterations caused by age, diabetes or surgical damage [476-480]. No data exist in humans. In humans, a RCT has shown that there is no clinically beneficial effect on endothelial dysfunction measured by flow-mediated dilation deriving from daily tadalafil when compared to placebo [481].

From a clinical standpoint, in 2007, tadalafil 2.5 and 5 mg/day were approved by the EMA for treatment of ED. According to the EMA, a once-daily regimen with tadalafil 2.5 or 5 mg might be considered suitable, based on patients’ choice and physicians’ judgement. In these patients, the recommended dose is 5 mg, taken once daily at approximately the same time. Overall, tadalafil, 5 mg once daily, provides an alternative to on-demand tadalafil for couples who prefer spontaneous rather than scheduled sexual activities or who anticipate frequent sexual activity, with the advantage that dosing and sexual activity no longer need to be linked. Overall, treatment with tadalafil 5 mg once daily in men complaining of ED of various severities is well-tolerated and effective [482].

An integrated analysis showed that, regardless of the type of ED population, there is no clinically significant difference between a tadalafil treatment administered with continuous (once daily) vs. on-demand regimen [481]. The appropriateness of the continuous use of a daily regimen should be re-assessed periodically [482,483].

Table 12: Summary of the key pharmacokinetic data for the four PDE5Is currently EMA-approved to treat ED*

Parameter | Sildenafil, 100 mg | Tadalafil, 20 mg | Vardenafil, 20 mg | Avanafil, 200mg |

Cmax | 560 μg/L | 378 μg/L | 18.7 μg/L | 5.2 μg/L |

Tmax (median) | 0.8-1 hours | 2 hours | 0.9 hours | 0.5-0.75 hours |

T1/2 | 2.6-3.7 hours | 17.5 hours | 3.9 hours | 6-17 hours |

AUC | 1,685 μg.h/L | 8,066 μg.h/L | 56.8 μg.h/L | 11.6 μg.h/L |

Protein binding | 96% | 94% | 94% | 99% |

Bioavailability | 41% | NA | 15% | 8-10% |

* Fasted state, higher recommended dose. Data adapted from EMA statements on product characteristics.Cmax = maximal concentration; Tmax = time-to-maximum plasma concentration; T1/2 = plasma elimination halftime; AUC = area under curve or serum concentration time curve.

Table 13: Common adverse events of the four PDE5Is currently EMA-approved to treat ED*

Adverse event | Sildenafil | Tadalafil | Vardenafil | Avanafil, 200mg |

Headache | 12.8% | 14.5% | 16% | 9.3% |

Flushing | 10.4% | 4.1% | 12% | 3.7% |

Dyspepsia | 4.6% | 12.3% | 4% | uncommon |

Nasal congestion | 1.1% | 4.3% | 10% | 1.9% |

Dizziness | 1.2% | 2.3% | 2% | 0.6% |

Abnormal vision | 1.9% | < 2% | None | |

Back pain | 6.5% | < 2% | ||

Myalgia | 5.7% | < 2% |

* Adapted from EMA statements on product characteristics.Safety issues for PDE5Is

(i) Cardiovascular safety

Clinical trial results for the four PDE5Is and post-marketing data of sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil have demonstrated no increase in myocardial infarction rates in patients receiving PDE5Is, as part of either RCTs or open-label studies, or compared to expected rates in age-matched male populations. None of the PDE5Is has an adverse effect on total exercise time or time-to-ischaemia during exercise testing in men with stable angina [442,484]. Chronic or on-demand use is well-tolerated with a similar safety profile. The prescription of all PDE5Is in patients with CVD or in those with high CV risk should be based on the recommendations of the 3rd Princeton Consensus Panel [410].

(ii) Contraindication for the concomitant use of organic nitrates

An absolute contraindication to PDE5Is is use of any form of organic nitrate (e.g., nitroglycerine, isosorbide mononitrate, and isosorbide dinitrate) or NO donors (e.g., other nitrate preparations used to treat angina, as well as amyl nitrite or amyl nitrate such as “poppers” that are used for recreation). They result in cGMP accumulation and unpredictable falls in blood pressure and symptoms of hypotension. The duration of interaction between organic nitrates and PDE5Is depends upon the PDE5I and nitrate used. If a PDE5I is taken and the patient develops chest pain, nitroglycerine must be withheld for at least 24 hours if sildenafil (and probably also vardenafil) is used (half-life, 4 hours), or at least 48 hours if tadalafil is used (half-life, 17.5 hours), and for no less than 12 hours if avanafil is used (half-life, 6-17 hours) [485-488].

(iii) Use caution with antihypertensive drugs

Co-administration of PDE5Is with antihypertensive agents (e.g., angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers, calcium blockers, β-blockers, and diuretics) may result in small additive decreases in blood pressure, which are usually minor [410]. In general, the adverse event profile of a PDE5I is not worsened by a background of antihypertensive medication, even when the patient is taking several antihypertensive agents [489].

(iv) Interaction with nicorandil

In vitro studies in animals suggest that the potassium channel opener nicorandil may potentiate the vasorelaxation induced by isoproterenol in isolated rat aorta by increasing cyclic GMP levels [490]. This may be due to the nitric oxide donating properties of nicorandil. Therefore, concurrent use of nicorandil and PDE5Is is also contraindicated.

α-Blocker interactions

Tadalafil 5 mg is currently the only licensed drug for the treatment of both ED and LUTS with level 1 evidence confirming its overall good efficacy in relieving urinary symptoms and improving erectile function [458]. As such, this treatment should be considered in patients suffering from mild to moderate LUTS associated with ED either alone or in combination with alpha-blockers. To this regard, given that both drugs are vasodilators with a potential risk of hypotension, historically there has always been caution in the combination of alpha-blockers and PDE5I (any) because of the fear of possible cumulative effects on blood pressure, based on the evidence from some individual studies that reported the tolerability of combination therapy [446,461,491]. However, a recent meta-analysis concluded that a concomitant treatment with α-blockers [both non-uroselective (e.g., terazosin and doxazosin) and uro-selective (e.g., alfuzosin, tamsulosin and silodosin)] and PDE5Is may produce changes in haemodynamic parameters, but it does not increase the rate of adverse events due to hypotension [491]. Therefore, there is no current limitation in the simultaneous use of α-blockers and PDE5I, prioritising the use of uro-selective drugs in order to further minimise the risk of dizziness or other adverse events, thus including hypotension.

Dosage adjustment

Drugs that inhibit the CYP34A pathway inhibit the metabolic breakdown of PDE5Is, thus increasing PDE5Is blood levels (e.g., ketoconazole, ritonavir, atazanavir, clarithromycin, indinavir, itraconazole, nefazodone, nelfinavir, saquinavir and telithromycin). Therefore, lower doses of PDE5Is are necessary. However, other agents, such as rifampin, phenobarbital, phenytoin and carbamazepine, may induce CYP3A4 and enhance the breakdown of PDE5Is, so that higher doses of PDE5Is are required. Severe kidney or hepatic dysfunction may require dose adjustments or warnings.

Management of non-responders to PDE5Is

The two main reasons why patients fail to respond to a PDE5I are either incorrect drug use or lack of efficacy. Data suggest that an adequate trial involves at least six attempts with a particular drug [492]. The management of non-responders depends upon identifying the underlying cause [493].

Check that the medication has been properly prescribed and correctly used. The main reason why patients fail to use their medication correctly is inadequate counselling from their physician. The most common causes of incorrect drug use are: i) failure to use adequate sexual stimulation; ii) failure to use an adequate dose; and, iii) failure to wait an adequate amount of time between taking the medication and attempting sexual intercourse.

Check that the patient has been using a licensed medication. There is a large counterfeit market in PDE5Is. The amount of active drug in these medications varies enormously and it is important to check how and from which source the patient has obtained his medication.

PDE5I action is dependent on the release of NO by the parasympathetic nerve endings in the erectile tissue of the penis. The usual stimulus for NO release is sexual stimulation, and without adequate sexual stimulation (and NO release), the medication is ineffective. Furthermore, the reduced production of NO that occurs in diabetic patients due to peripheral neuropathy, is thought to be the justification for the higher failure rate of PDE5Is in this category of patients. Oral PDE5Is take different times to reach maximal plasma concentrations (Cmax) [446,448,464,471,494-496]. Although pharmacological activity is achieved at plasma levels below the maximal plasma concentration, there will be a period of time following oral ingestion of the medication during which the drug is ineffective. Even though all four drugs have an onset of action in some patients within 15-30 minutes of oral ingestion [448,464,494-496], most patients require a longer delay between taking the medication [462,471,497,498]. Absorption of both sildenafil and vardenafil can be delayed by a heavy, fatty meal [499]. Absorption of tadalafil is less affected, and food has negligible effects on its bioavailability [494]. When avanafil is taken with a high-fat meal, the rate of absorption is reduced with a mean delay in Tmax of 1.25 hours and a mean reduction in Cmax of 39% (200 mg). There is no effect on the extent of exposure (area under the curve). The small changes in avanafil Cmax are considered to be of minimal clinical significance [467,468,471].

It is possible to wait too long after taking the medication before attempting sexual intercourse. The half-life of sildenafil and vardenafil is ~4 hours, suggesting that the normal window of efficacy is 6-8 hours following drug ingestion, although responses following this time period are recognised. The half-life of avanafil is

6-17 hours. Tadalafil has a longer half-life of ~17.5 hours, so the window of efficacy is longer at ~36 hours. Data from uncontrolled studies suggest patient education can help salvage an apparent non-responder to a PDE5I [493,500-503]. After emphasising the importance of dose, timing, and sexual stimulation to the patient, erectile function can be effectively restored following re-administration of the relevant PDE5I [493,500,501].

A systematic review has addressed the association between genetic polymorphism, especially those encoding endothelial NO synthase, and the variability in response to PDE5Is [504]. Similar data have suggested that response to sildenafil treatment is also dependent on polymorphism in the PDE5A gene, which encodes the principal cGMP-catalysing enzyme in the penis, regulating cGMP clearance, and it is the primary target of sildenafil [505-507].

Clinical strategies in patients correctly using a PDE5Is

Overall, treatment goals should be individualised to restore sexual satisfaction for patients and/or couples, and improve QoL based on patients’ expressed needs and desires [508]. In this context, data suggests that almost half of patients abandon first-generation PDE5Is within 1 year, with no single specific factor playing a major role in dropout rates [509].

Uncontrolled trials have demonstrated that hypogonadal patients not responding to PDE5Is may improve their response to PDE5Is after initiating testosterone therapy [55,439,510]. Therefore, in the real-life setting most patients with ED will first be prescribed a PDE5I, which is usually effective; however, if diagnostic criteria suggestive for testosterone deficiency are present, testosterone therapy may be more appropriate even in ED patients [5,55].

Modification of other risk factors may also be beneficial, as previously discussed. Limited data suggest that some patients might respond better to one PDE5I than to another [511], and although these differences might be explained by variations in drug pharmacokinetics, they do raise the possibility that, despite an identical mode of action, switching to a different PDE5I might be helpful. However it is important to emphasise that the few randomised studies have shown any difference in clinical outcomes with different drugs and intake patterns in patients with classic ED [512] and in special populations such as people with diabetics [513].

In refractory, complex, or difficult-to-treat cases of ED patients a combination therapy should be considered as a first-line approach. Although the available data are still limited, combining PDE5I with antioxidant agents, LI-SWT or a vacuum erection device (VED) improves efficacy outcomes, without any significant increase in adverse events [514]. Similarly, the association of daily tadalafil with a short-acting PDE5I (such as sildenafil) leads to improved outcomes, without any significant increase in adverse effects [515].

5.6.2.2. Topical/Intraurethral alprostadil

The vasoactive agent alprostadil can be administered intraurethrally with two different formulations. The first delivery method is topical, using a cream that includes a permeation enhancer to facilitate absorption of alprostadil (200 and 300 μg) via the urethral meatus [516,517]. Clinical data are still limited. Significant improvement compared to placebo was recorded for IIEF-EF domain score, SEP2 and SEP3 in a broad range of patients with mild-to-severe ED [518]. Adverse effects include penile erythema, penile burning, and pain that usually resolve within 2 hours of application. Systemic adverse effects are rare. Topical alprostadil (VITAROS™) at a dose of 300 μg is available in some European countries. Recently, a randomised cross-over clinical trial has shown that, compared to the standard administration route, direct delivery within the urethral meatus can increase efficacy and confidence among patients, without increasing adverse effects [519].

The second delivery method is by intra-urethral insertion of a specific formulation of alprostadil (125-1000 μg) in a medicated pellet (MUSE™) [229]. Erections sufficient for intercourse are achieved in 30-65.9% of patients. In clinical practice, it is recommended that intra-urethral alprostadil is initiated at a dose of 500 μg, as it has a higher efficacy than the 250 μg dose, with minimal differences with regards to adverse events. In case of unsatisfactory clinical response, the dose can be increased to 1000 μg [520-522]. The application of a constriction ring at the root of the penis may improve efficacy [521,522].

Overall, the most common adverse events are local pain (29-41%) and dizziness with possible hypotension (1.9-14%). Penile fibrosis and priapism are rare (< 1%). Urethral bleeding (5%) and urinary tract infections (0.2%) are adverse events related to the mode of administration. Efficacy rates are significantly lower than for intracavernous pharmacotherapy [523], with ~30% adherence to long-term therapy. Intraurethral pharmacotherapy provides an alternative to intracavernous injections in patients who prefer a less-invasive, although less-efficacious treatment.

5.6.2.3. Psychosocial intervention and therapy

Psychosocial interventions including different modalities (e.g., sexual skills training, marital therapy, psychosexual education) [436], and Cognitive and Behavioural Therapy (CBT - group or couple format), are recommended [430]. Cognitive and Behaviour Therapy is aimed at altering dysfunctional cognitive and behavioural patterns influencing ED, and increasing adjustment during the course of the disorder. Some of its techniques include identifying triggers preceding erectile difficulties, cognitive restructuring of dysfunctional thinking styles, learning coping skills aimed at dealing with erectile difficulties and emotional symptoms, improving communications skills with the partner, and relapse prevention. The CBT approach combined with medical treatment for ED has received empirical support and is considered an optimal procedure [524]. Moreover, there is preliminary evidence supporting the role of mindfulness-based therapy for ED and associated outcomes such as sexual satisfaction [525].

5.6.2.4. Hormonal treatment

The advice of an endocrinologist should be sought for managing patients with certain hormonal abnormalities or endocrinopathies [401]. Hypogonadism is either a result of primary testicular failure or secondary to pituitary/hypothalamic causes (e.g., a functional pituitary tumour resulting in hyperprolactinaemia) [401,526]. When clinically indicated [527], testosterone therapy (intramuscular, transdermal, or oral) can be considered for men with low or low-normal testosterone levels and concomitant problems with their sexual desire, EF and dissatisfaction derived from intercourse and overall sex life (see Section 3.6 for a comprehensive discussion of testosterone therapy).

5.6.2.5. Vacuum erection devices

Vacuum erection devices provide passive engorgement of the corpus cavernosum, together with a constrictor ring placed at the base of the penis to retain blood within the corpus. Published data report that efficacy, in terms of erections satisfactory for intercourse, is as high as 90%, regardless of the cause of ED and satisfaction rates range between 27% and 94% [528,529]. Most men who discontinue use of VEDs do so within 3 months. Long-term use of VEDs decreases to 50-64% after 2 years [530]. The most common adverse events include pain, inability to ejaculate, petechiae, bruising, and numbness [529]. Serious adverse events (skin necrosis) can be avoided if patients remove the constriction ring within 30 minutes. Vacuum erection devices are contraindicated in patients with bleeding disorders or on anticoagulant therapy [531,532]. Vacuum erection devices may be the treatment of choice in well-informed older patients with infrequent sexual intercourse and co-morbidity requiring non-invasive, drug-free management of ED [528,529,533].

5.6.2.6. Intracavernous injections therapy

Intracavernous administration of vasoactive drugs was the first medical treatment introduced for ED [503,534]. According to invasiveness, tolerability, effectiveness and patients’ expectations (Figure 6), patients may be offered intracavernous injections at every stage of a tailored treatment work-up. The success rate is high (85%) [523,535].

5.6.2.6.1. Alprostadil

Alprostadil (CaverjectTM, Edex/ViridalTM) was the first and only drug approved for intracavernous treatment of ED [503,536]. Intracavernous alprostadil is most efficacious as a monotherapy at a dose of 5-40 μg (40 μg may be offered off label in some European countries). The erection appears after 5-15 minutes and lasts according to the dose injected, but with significant heterogeneity among patients. An office-training programme is required for patients to learn the injection technique. In men with limited manual dexterity, the technique may be taught to their partners. The use of an automatic pen that avoids a view of the needle may be useful to resolve fear of penile puncture and simplifies the technique.

Efficacy rates for intracavernous alprostadil of > 70% have been found in the general ED population, as well as in patient subgroups (e.g., men with diabetes or CVD), with reported satisfaction rates of 87-93.5% in patients and 86-90.3% in partners after the injections [503,534]. Complications of intracavernous alprostadil include penile pain (50% of patients reported pain only after 11% of total injections), excessively prolonged and undesired erections (5%), priapism (1%), and fibrosis (2%) [503,534,537]. Pain is usually self-limited after prolonged use and it can be alleviated with the addition of sodium bicarbonate or local anaesthesia [503,534,538]. Cavernosal fibrosis (from a small haematoma) usually clears within a few months after temporary discontinuation of the injection programme. However, tunical fibrosis suggests early onset of Peyronie’s disease and may indicate stopping intracavernous injections indefinitely. Systemic adverse effects are uncommon. The most common is mild hypotension, especially when using higher doses. Contraindications include men with a history of hypersensitivity to alprostadil, men at risk of priapism, and men with bleeding disorders. Despite these favourable data, drop-out rates of 41-68% have been reported for intracavernous pharmacotherapy [503,534,539,540], with most discontinuations occurring within the first 2-3 three months. In a comparative study, alprostadil monotherapy had the lowest discontinuation rate (27.5%) compared to overall drug combinations (37.6%), with an attrition rate after the first few months of therapy of 10% per year [541]. Reasons for discontinuation included desire for a permanent mode of therapy (29%), lack of a suitable partner (26%), poor response (23%) (especially among early drop-out patients), fear of needles (23%), fear of complications (22%), and lack of spontaneity (21%). Careful counselling of patients during the office-training phase as well as close follow-up are important in addressing patient withdrawal from an intracavernous injection programme [542-544].

5.6.2.6.2. Combination therapy

Table 14 details the available intracavernous injection therapies (compounds and characteristics). Combination therapy enables a patient to take advantage of the different modes of action of the drugs being used, as well as alleviating adverse effects by using lower doses of each drug.

- Papaverine (20-80 mg) was the first oral drug used for intracavernous injections. It is most commonly used in combination therapy because of its high incidence of adverse effects as monotherapy. Papaverine is currently not licensed for treatment of ED.

- Phentolamine has been used in combination therapy to increase efficacy. As monotherapy, it produces a poor erectile response.

- Sparse data in the literature support the use of other drugs, such as vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), NO donors (linsidomine), forskolin, potassium channel openers, moxisylyte or calcitonin gene-related peptide, usually combined with the main drugs [545,546]. Most combinations are not standardised and some drugs have limited availability worldwide.

- Bimix, Trimix: papaverine (7.5-45 mg) plus phentolamine (0.25-1.5 mg) (also known as Bimix), and papaverine (8-16 mg) plus phentolamine (0.2-0.4 mg) plus alprostadil (10-20 μg) (also known as Trimix), have been widely used with improved efficacy rates, although they have never been licensed for ED [547,548]. Trimix has the highest efficacy rates, reaching 92%; this combination has similar adverse effects as alprostadil monotherapy, but a lower incidence of penile pain due to lower doses of alprostadil. However, fibrosis is more common (5-10%) when papaverine is used (depending on total dose).

- InvicorpTM: Vasoactive intestinal peptide (25 μg) plus phentolamine mesylate (1-2 mg Invicorp), currently licensed in Scandinavia, is a combination of two active components with complementary modes of action. Clinical studies have shown that the combination is effective for intracavernous injections in

> 80% of men with ED, including those who have failed to respond to other therapies and, unlike existing intracavernous therapies, is associated with a low incidence of penile pain and a virtually negligible risk of priapism [549].

Despite high efficacy rates, 5-10% of patients do not respond to combination intracavernous injections. The combination of sildenafil with intracavernous injection of the triple combination regimen may salvage as many as 31% of patients who do not respond to the triple combination alone [550]. However, combination therapy is associated with an increased incidence of adverse effects in 33% of patients, including dizziness in 20% of patients. This strategy can be considered in carefully selected patients before proceeding to a penile implant.

Table 14: Intracavernous injection therapy - compounds and characteristics

Name | Substance | Dosage | Efficacy | Adverse Events | Comment |

Caverject™ or Edex/Viridal™ | Alprostadil | 5-40 µg/mL | ~ 70% | Penile pain, priapism, fibrosis | Easily available |

Papaverine | Papaverine | 20 - 80 mg | < 55% | Elevation of liver enzymes, priapism, fibrosis | Abandoned as monotherapy |

Phentolamine | Phentolamine | 0.5 mg/mL | Poor efficacy as monotherapy | Systemic hypotension, reflex tachycardia, nasal congestion, and gastrointestinal upset | Abandoned as monotherapy |

Bimix | Papaverine + Phentolamine | 30 mg/mL + 0.5 mg/mL | ~ 90% | Similar to Alprostadil (less pain) | Not licensed for the treatment of ED |

Trimix | Papaverine + Phentolamine + Alprostadil | 30 mg/mL + 1 mg/mL + 10 µg/mL | ~ 92% | Similar as Alprostadil (less pain) | Not licensed for the treatment of ED |

Invicorp™ | Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) + Phentolamine | 25 µg + 1-2 mg | ~ 80% | Similar as Alprostadil without pain | Easily available |

There are currently several potential novel treatment modalities for ED, from innovative vasoactive agents and trophic factors to stem cell therapy and gene therapy. Most of these therapeutic approaches require further investigation in large-scale, blinded, placebo-controlled randomised studies to achieve adequate evidence-based and clinically-reliable recommendation grades [551-556]. A systematic review has concluded that five completed human clinical trials have shown promise for stem cell therapy as a restorative treatment for ED [557].

5.6.2.7. Regeneration therapies

5.6.2.7.1. Shockwave therapy

The use of LI-SWT has been increasingly proposed as a treatment for vasculogenic ED over the last decade, being the only currently marketed treatment that might offer a cure, which is the most desired outcome for most men suffering from ED [418,558-565].