8. PENILE CURVATURE

8.1. Congenital penile curvature

8.1.1. Epidemiology/aetiology/pathophysiology

Congenital penile curvature (CPC) is a rare condition, with a reported incidence of < 1% [1018], although some studies have reported higher prevalence rates of 4-10%, in the absence of hypospadias [1019]. Congenital penile curvature results from disproportionate development of the tunica albuginea of the corporal bodies and is not associated with urethral malformation. In most cases, the curvature is ventral, but it can also be lateral and, more rarely, dorsal [1020].

8.1.2. Diagnostic evaluation

Taking a medical and sexual history is usually sufficient to establish a diagnosis of CPC. Patients usually present after reaching puberty as the curvature becomes more apparent with erections, and more severe curvatures can make intercourse difficult or impossible. Physical examination and photographic documentation during erection (preferably after intracavernous injection [ICI] of vasoactive drugs) are both mandatory to document the curvature and exclude other pathologies [1020].

8.1.3. Disease management

The definitive treatment for this disorder remains surgical and can be deferred until after puberty, although a survey has suggested that men with probable untreated ventral penile curvature report more dissatisfaction with penile appearance, increased difficulty with intercourse, and psychological problems; therefore, supporting surgical correction of CPC in childhood [1021]. Surgical treatments for CPC generally share the same principles as in Peyronie’s disease. Plication techniques (Nesbit, 16-dot, Yachia, Essed-Schröeder, and others) with or without neurovascular bundle elevation (medial/lateral) and with or without complete penile degloving, have been described [1022-1031]. Other approaches are based on corporal body de-rotation proposed by Shaeer with different technical refinements that enable correction of a ventral curvature, with reported minimal narrowing and shortening [1032-1035]. There are no direct comparative studies therefore no single technique can be advocated as superior in terms of surgical correction.

8.1.4. Summary of evidence for congenital penile curvature

Summary of evidence | LE |

Medical and sexual history are usually sufficient to establish a diagnosis of CPC. Physical examination and photographic documentation during erection (preferably after intracavernous injection [ICI] of vasoactive drugs) are both mandatory to document the curvature | 3 |

There is no role for medical management of CPC. Surgery is the only treatment option, which can be deferred until after puberty and can be performed at any time in adult life in individuals with significant functional impairment during intercourse. | 3 |

8.1.5. Recommendation for the treatment congenital penile curvature

Recommendation | Strength rating |

Use plication techniques with or without neurovascular bundle dissection (medial/lateral) for satisfactory curvature correction, although there is currently no optimum surgical technique. | Strong |

8.2. Peyronie’s Disease

8.2.1. Epidemiology/aetiology/pathophysiology

8.2.1.1. Epidemiology

Epidemiological data on Peyronie’s disease (PD) are limited. Prevalence rates of 0.4-20.3% have been published, with a higher prevalence in patients with ED and diabetes [1036-1044]. A recent survey has indicated that the prevalence of definitive and probable cases of PD in the USA is 0.7% and 11%, respectively, suggesting that PD is an under-diagnosed condition [1045]. Peyronie’s disease often occurs in older men with a typical age of onset of 50-60 years. However, PD also occurs in younger men (< 40 years), but at a lesser prevalence than in older men (1.5-16.9%) [1040,1046,1047].

8.2.1.2. Aetiology

The aetiology of PD is unknown. However, repetitive microvascular injury or trauma to the tunica albuginea is still the most widely accepted hypothesis to explain the aetiology [1048]. Abnormal wound healing leads to the remodelling of connective tissue into a fibrotic plaque [1048-1050]. Penile plaque formation can result in a curvature, which, if severe, may impair penetrative sexual intercourse. The genetic underpinnings of fibrotic diatheses, including PD and Dupuytren’s disease, are beginning to be understood, although much of the data are contradictory and we do not yet have the basis for predicting who will develop the disease or disease severity (Table 23) [1051,1052].

Table 23: Genes with involvement in Peyronie’s and Dupuytren’s diseases (adapted from Herati et al., )

Gene | Gene Symbol | Chromosomal Location | Gene Function |

Matrix metalloproteinase 2 | MMP 2 | 16q12.2 | Breakdown of extracellular matrix |

Matrix metalloproteinase 9 | MMP 9 | 20q13.12 | Breakdown of extracellular matrix |

Thymosin beta-10 | TMSB-10 | 2p11.2 | Prevents spontaneous globular actin monomer polymerisation |

Thymosin beta-4 | TMSB-4 | Xq21.3-q22 | Actin sequestering protein |

Cortactin; amplaxin | CTTN | 11q13 | Organises cytoskeleton and cell adhesion structures |

Transforming protein RhoA H12 | RHOA | 3p21.3 | Regulates cytoskeletal dynamics |

RhoGDP dissociation inhibitor | ARHGDIA | 17q25.3 | Regulates Rho GTPase signaling |

Pleiotrophin precursors; osteoblast specific factor 1 | PTN/OSF-1 | 7q33 | Stimulates mitogenic growth of fibroblasts and osteoblasts |

Amyloid A4 protein precursor; nexin II | PN-II | 21q21.3 | Cell surface receptor |

Defender against cell death 1 | DAD1 | 14q11.2 | Prevents apoptosis |

Heat Shock 27-kDa protein (HSP27) | HSP27 | 7q11.23 | Actin organisation and translocation from cytoplasm to nucleus upon |

Macrophage-specific stimulating factor | MCSF/CSF1 | 1p13.3 | Controls the production, differentiation and function of macrophages |

Transcription factor AP-1 | AP1 | 1p32-p31 | Key mediator of macrophage education and point of recruitment for immunosuppressive regulatory T cells |

Human Early growth response protein 1 | hEGR1 | 5q31.1 | Promotes mitosis |

Monocyte chemotactic protein 1 | MCP1 | 17q11.2-q12 | Chemotactic cytokine for monocytes and basophils |

Bone Proteoglycan II precusor; Decorin | DCN | 12q21.33 | Matrix proteoglycan |

T-Cell specific rantes protein precursor | RANTES | 17q12 | Chemoattractant for monocytes, memory T cells and eosinophils |

Integrin Beta-1 | ITGB1 | 10p11.2 | Membrane receptor involved in cell adhesion and recognition in a variety of processes including immune response, tissue repair and haemostasis |

Osteonectin | SPARC | 5q31.3-q32 | Matrix protein that facilitates collagen ossification |

Ubiquitin | RBX1 | 6q25.2-q27 | Targets substrate proteins for proteasomal degradation |

Transcription factor ATF-4 | ATF4 | 22q13.1 | Transcriptional regulation of osteoblasts and down-regulates apelin to promote apoptosis |

Elastase IIB | ELA2B | 1p36.21 | Serine protease that hydrolyses matrix protein |

c-myc | MYC | 8q24.21 | Transcription factor that regulates cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and cellular transformations |

60 S ribosomal protein L13A | RPL13A | 19q13.3 | Repression of inflammatory genes |

Prothymosin alpha | PTMA | 2q37.1 | Influences chromatin remodeling, anti-apoptotic factor |

Fibroblast tropomyosin | TPM1 | 15q22.1 | Actin-binding protein involved in contractile system of striated and smooth muscle |

Myosin light chain | MYL2 | 12q24.11 | Regulatory light chain associated with myosin Beta heavy chain |

Filamin | FLN | Xq28 | Actin-binding protein that crosslinks actin filaments and links actin to membrane glycoproteins. Interacts with integrins |

Calcineurin A subunit alpha | PPP3CA | 4q24 | Promotes cell migration and invasion and inhibits apoptosis |

DNA binding protein inhibitor Id-2 | ID2 | 2p25 | Transcriptional regulator that inhibits the function of basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors by preventing their heterodimerisation, negatively regulates cell differentiation |

Smooth muscle gamma actin | ACTA2 | 10q23.3 | Plays a role in cell motility, structure and integrity |

Desmin | DES | 2q35 | Forms intra-cytoplasmic filamentous network connecting myofibrils |

Cadherin FIB2 | PCDHGB4 | 5q31 | Cell adhesion proteins expressed in fibroblasts and playing a role in wound healing |

Cadherin FIB1 | DCHS1 | 11p15.4 | Cell adhesion proteins expressed in fibroblasts and playing a role in wound healing |

SMAD family member 7 | SMAD7 | 18q21.1 | Interacts with and promotes degradation of TGFBR1 |

Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 6 | IGFBP6 | 12q13 | Negative regulator of cellular senescence inhuman fibroblasts |

Collagen 1 alpha | COL1A1 | 17q21.33 | Encodes pro-alpha 1 chains of type 1 collagen |

Transforming growth factor, beta 1 | TGFB1 | 19q13.1 | Cytokine that regulates proliferation, differentiation, adhesion and cell migration |

8.2.1.3. Risk factors

The associated co-morbidities and risk factors, most commonly reported, are diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemias, ischaemic cardiopathy, autoimmune diseases [1053], ED, smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, low testosterone levels and pelvic surgery (e.g., radical prostatectomy) [357,1040,1044,1054-1056]. Dupuytren’s contracture is more common in patients with PD affecting 8.3-39% of patients [1041,1057-1059], while 4-26% of patients with Dupuytren’s contracture report PD [1058,1060,1061].

8.2.1.4. Pathophysiology

Two phases of the disease can be distinguished [1062]. The first is the active inflammatory phase (acute phase), which may be associated with painful erections and a palpable nodule or plaque in the tunica of the penis; typically, but not invariably, a penile curvature begins to develop. The second is the fibrotic phase (chronic phase) with the formation of hard, palpable plaques that can calcify, with stabilisation of the disease and of the penile deformity. With time, the penile curvature is expected to worsen in 21-48% of patients or stabilise in 36-67% of patients, while spontaneous improvement has been reported in only 3-13% of patients [1054,1063-1065]. Overall, penile deformity is the most common first symptom of PD (52-94%). Pain is the second most common presenting symptom of PD, which presents in 20-70% of patients during the early stages of the disease [1066]. Pain tends to resolve with time in 90% of men, usually during the first 12 months after the onset of the disease [1063,1064]. Palpable plaques have been reported as an initial symptom in 39% of the patients and mostly situated dorsally [50,1066].

In addition to functional effects on sexual intercourse, men may also suffer from significant psychological distress. Validated mental health questionnaires have shown that 48% of men with PD have moderate or severe depression, sufficient to warrant medical evaluation [1067].

8.2.1.5. Summary of evidence on epidemiology/aetiology/pathophysiology of Peyronie’s disease

Summary of evidence | LE |

Peyronie’s disease (PD) is a connective tissue disorder, characterised by the formation of a fibrotic lesion or plaque in the tunica albuginea, which may lead to penile deformity. | 2b |

The contribution of associated co-morbidity or risk factors (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, lipid abnormalities and Dupuytren’s contracture) to the pathophysiology of PD is still unclear. | 3 |

Two phases of the disease can be distinguished. The first phase is the active inflammatory phase (acute phase - painful erections, nodule/plaque), and the second phase is the fibrotic/calcifying phase (chronic or stable phase) with formation of hard palpable plaques (disease stabilisation). | 2b |

Spontaneous resolution is uncommon (3-13%) and most patients experience disease progression (21-48%) or stabilisation (36-67%). Pain is usually present during the early stages of the disease, but tends to resolve with time in 90% of men within 12 months of onset. | 2a |

8.2.2. Diagnostic evaluation

The aim of the initial evaluation is to obtain information on the presenting symptoms and their duration (e.g., pain on erection, palpable nodules, deformity, length and girth and erectile function). It is important to obtain information on the distress caused by the symptoms and the potential risk factors for ED and PD. A disease-specific questionnaire (Peyronie’s disease questionnaire [PDQ]) has been developed for use in clinical practice and trials. Peyronie’s disease questionnaire measures three domains, including psychological and physical symptoms, penile pain and symptom bother [1068].

Clinicians should take a focused history to distinguish between active and stable disease, as this will influence medical treatment or the timing of surgery. Patients who are still likely to have active disease are those with a shorter symptom duration, pain on erection, or a recent change in penile deformity. Resolution of pain and stability of the curvature for at least 3 months are well-accepted criteria of disease stabilisation as well as patients’ referral for specific medical therapy [1069,1070] or surgical intervention, when indicated [1071].

The examination should start with a focused genital assessment that is extended to the hands and feet for detecting possible Dupuytren’s contracture or Ledderhosen scarring of the plantar fascia [1064]. Penile examination is performed to assess the presence of a palpable nodule or plaque. There is no correlation between plaque size and degree of curvature [1072]. Measurement of the stretched or erect penile length is important because it may have an impact on the subsequent treatment decisions and potential medico-legal implications [1073-1075].

An objective assessment of penile curvature with an erection is mandatory. According to current literature, this can be obtained by several approaches, including home (self) photography of a natural erection (preferably), using a vacuum-assisted erection test or an ICI using vasoactive agents. However, it has been suggested that the ICI method is superior, as it is able to induce an erection similar to or better than that which the patient would experience when sexually aroused [1076-1078]. Computed tomography and MRI have a limited role in the diagnosis of the curvature and are not recommended on a routine basis. Erectile function can be assessed using validated instruments such as the IIEF although this has not been validated in PD patients [1079]. Erectile dysfunction is common in patients with PD (30-70.6%) [1080,1081]. Although ED is mainly believed to be due to an arterial or cavernosal (veno-occlusive) dysfunction in patients with PD [1054,1072,1082], recent papers fail to demonstrate any impact of the direction and the severity of penile curvature on ED in patients with PD [1083]. The presence of ED and psychological factors may also have a profound impact on the treatment strategy [1084]. Ultrasound measurement of plaque size is not accurate but it could be helpful to assess the presence of the plaque and its calcification and location [1085,1086]. Doppler US may be used for the assessment of penile haemodynamics and ED aetiology [1081].

8.2.2.1. Summary of evidence for diagnosis of Peyronie’s disease

Summary of evidence | LE |

Ultrasound measurement of plaque size is inaccurate and operator dependent. | 3 |

Doppler US may be used to assess penile haemodynamic and vascular anatomy. | 2a |

Intracavernous injection method is superior to other methods to provide an objective assessment of penile curvature with an erection. | 4 |

8.2.2.2. Recommendations for diagnosis of Peyronie’s disease

Recommendations | Strength rating |

Take a medical and sexual history of patients with Peyronie’s disease (PD), include duration of the disease, pain on erection, penile deformity, difficulty in vaginal/anal intromission due to disabling deformity and erectile dysfunction (ED). | Strong |

Take a physical examination, including assessment of palpable plaques, stretched or erect penile length, degree of curvature (self-photography, vacuum-assisted erection test or pharmacological-induced erection) and any other related diseases (e.g., Dupuytren’s contracture, Ledderhose disease) in patients with PD. | Strong |

Use the intracavernous injection (IC) method in the diagnostic work-up of PD to provide an objective assessment of penile curvature with an erection. | Weak |

Use the PD specific questionnaire especially in clinical trials, but mainstream usage in daily clinical practice is not mandatory. | Weak |

Do not use ultrasound (US), computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging to assess plaque size and deformity in routine clinical practice. | Weak |

Use penile Doppler US in the case of diagnostic evaluation of ED, to evaluate penile haemodynamic and vascular anatomy, and to assess location and calcification of plaques, especially prior to surgery. | Weak |

8.2.3. Disease management

8.2.3.1. Conservative treatment

Conservative treatment of PD is primarily focused on patients in the early stage of the disease as an adjunct treatment to relieve pain and prevent disease progression or if the patient declines other treatment options during the active phase [1064,1071]. Several options have been suggested, including oral pharmacotherapy, intralesional injection therapy, shockwave therapy (SWT) and other topical treatments (Table 24).

The results of the studies on conservative treatment for PD are often contradictory, making it difficult to provide recommendations in everyday, real-life settings [1087]. The Panel does not support the use of oral treatments for PD including pentoxifylline, vitamin E, tamoxifen, procarbazine, potassium para-aminobenzoate (potaba), omega-3 fatty acids or combination of vitamin E and L-carnitine because of their lack of efficacy (tamoxifen, colchicine, vitamin E and procarbazine) or evidence (potaba, L-carnitine and pentoxyfilline) [1071,1088-1090].

This statement is based on several methodological flaws in the available studies. These include their uncontrolled nature, the limited number of patients treated, the short-term follow-up and the different outcome measures used [1091,1092]. Even in the absence of adverse events, treatment with these agents may delay the use of other efficacious treatments.

Table 24: Conservative treatments for PD

Oral treatments |

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) |

Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (PDE5Is) |

Intralesional treatments |

Verapamil |

Nicardipine |

Clostridium collagenase |

Interferon α2B |

Hyaluronic acid |

Botulinum toxin |

Topical treatments |

H-100 gel |

Other |

Traction devices |

Multimodal treatment |

Extracorporeal shockwave treatment |

Vacuum Erection Device |

8.2.3.1.1. Oral treatment

Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors

Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors were first suggested as a treatment for PD in 2003 to reduce collagen deposition and increase apoptosis through the inhibition of transforming growth factor (TGF)-b1 [1093-1095]. A retrospective study of 65 men suggested the use of PDE5Is as an alternative for the treatment of PD. The results indicated that treatment with tadalafil was helpful in decreasing curvature and remodelling septal scars when compared to controls [1096]. Another recent study concluded that sildenafil was able to improve erectile function and pain in PD patients. Thirty-nine patients with PD were divided into two groups receiving vitamin E (400 IU) or sildenafil 50 mg for 12 weeks and significantly better outcomes in pain and IIEF score were seen in the sildenafil group [1097]. Findings from a recently published observational retrospective study involving patients in the acute phase of Peyronie’s disease and ED who have been treated with Tadalafil 5 mg once daily compared to patients with comparable baseline conditions who decided not to take the daily compound (i.e., 108 intervention vs. 83 controls) showed that treated men had lower curvature progression rates at 12 weeks (25.9% vs. 39.7%, p = 0.042) [1098]. Similarly, mean SHIM score and PDQ-Overall and PDQ-Penile Pain scores significantly improved in the intervention group (p < 0.001).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be offered to patients in active-phase PD in order to manage penile pain, which is usually present in this phase. Pain levels should be periodically reassessed in monitoring treatment efficacy.

8.2.3.1.2. Intralesional treatment

Injection of pharmacologically active agents directly into penile plaques represents another treatment option. It allows a localised delivery of a particular agent that provides higher concentrations of the drug inside the plaque. However, delivery of the compound to the target area is difficult to ensure, particularly when a dense or calcified plaque is present.

Calcium channel antagonists: verapamil and nicardipine

The rationale for intralesional use of channel antagonists in patients with PD is based on in vitro research [1099,1100]. Due to the use of different dosing schedules and the contradictory results obtained in published studies, the evidence is not strong enough to support the clinical use of injected channel blockers verapamil and nicardipine and the results do not demonstrate a meaningful improvement in penile curvature compared to placebo [1101-1106]. In fact, most of the studies did not perform direct statistical comparison between groups.

Collagenase of Clostridium histolyticum

Collagenase of Clostridium histolyticum (CCH) is a chromatographically purified bacterial enzyme that selectively attacks collagen, which is known to be the primary component of the PD plaque [1107-1110]. Intralesional injection of CCH has been used in the treatment of PD since 1985. In 2014 the EMA approved CCH for the nonsurgical treatment of the stable phase of PD in men with palpable dorsal plaques in whom abnormal curvature of 30-90o and non-ventrally located plaques are present. It should be administered by a healthcare professional who is experienced and properly trained in the administration of CCH treatment for PD [1111,1112].

The original treatment protocol in all studies consists of two injections of 0.58 mg of CCH 24-72 hours apart every 6 weeks for up to four cycles. Data from IMPRESS (Investigation for Maximal Peyronie´s Reduction Efficacy and Safety Studies) II and II studies [976], as well as post approval trials [1113], which demonstrated the efficacy and safety of this treatment, are summarised in Table 25.

Table 25: Clinical evidence supporting CCH treatment

Author/year [Ref] | Study type | Special considerations | No. of patients | No. of injections | Decrease in PC in CCH group |

Gelbard et al. (2013) [1114] | Phase 3 randomised double blinded controlled trial | Pilot study | 551 | 8 (in 78.8% of patients) | 34% (17.0 ± 14.8 degrees) |

Levine et al. (2015) [1115] | Phase 3 Open-label | IMPRESS based | 347 | < 8 | 34.4% (18.3 ± 14.02 degrees) |

Ziegelmann et al. (2016) [1116] | Prospective double-blinded trial | IMPRESS based | 69 | Mean = 6 | 38% (22.6 ± 16.2 degrees) |

Yang and Bennett (2016) [1117] | Prospective study | Included patients in acute phase | 37 in SP 12 in AP | Median in SP = 6 Median in AP = 2.5 | 32.4% (15.4 degrees) AP = 20 degrees |

Nguyen et al. (2017) [1079] | Retrospective study | Included patients in acute phase | 126 in SP 36 in AP | Mean = 3.2 | SP = 27.4% (15.2 ± 11.7 degrees) AP = 27.6% (18.5 ± 16.2 degrees) N/S differences in final change in curvature between group 1 (16.7º) and group 2 (15.6º) p = 0.654 |

Anaissie et al. (2017) [1118] | Retrospective study | Included patients in acute phase | 77 | Mean = 6.6 | 29.6% (15.3 ± 12.9 degrees) |

Abdel Raheem et al. (2017) [1119] | Prospective study | Shortened protocol | 53 | Mean = 3 | 31.4% (17.6 degrees) |

Capece et al. (2018) [1120] | Prospective multicentric study | Shortened protocol | 135 | Mean = 3 | 42.9% (19.1 degrees) |

SP = Stable phase; AP = Acute phase; N/S = Non-significant.

The average improvement in curvature was 34% compared to 18.2% in the placebo group. Three adverse events of corporeal rupture were surgically repaired. The greatest chance of curvature improvement is for curvatures between 30° and 60°, longer duration of disease, IIEF > 17, and no calcification [1070]. An 18.2% improvement from baseline in the placebo arm was also observed. These findings raise questions regarding the alleged role of plaque injection and penile modelling, regardless of the medication, in improving outcomes in men with PD as the placebo or modelling arm resulted in high curvature reduction compared to treatment.

The conclusion of the IMPRESS I and II studies is that that CCH improves PD both physically and psychologically [1114]. A post hoc meta-analysis of the IMPRESS studies demonstrated better results in patients with < 60° of curvature, > 2 years evolution, no calcification in the plaque and good erectile function [1113].

Thereafter, a modified short protocol consisting of administration of a single (0.9 mg, one vial) injection per cycle distributed along three lines around the point of maximum curvature up to three cycles, separated by 4-weekly intervals, has been proposed and rapidly popularised replacing physician modelling with a multi-modal approach through penile stretching, modelling and VED at home [1119]. The results from this modified protocol were comparable to the results of the IMPRESS trials and appeared to decrease the cost and duration of treatment, although these studies represent non-randomised study protocols. These results were further explored in a prospective non-randomised multi-centre study [982]. In another large single-arm multi-centre clinical study using the shortened protocol, longer PD duration, greater baseline PC and basal and dorsal plaque location were identified as clinically significant predictors of treatment success [1121]. Accordingly, a nomogram developed to predict treatment success after CCH for PD showed that patients with longer PD duration, greater baseline penile curvature and basal plaque location had a greater chance of treatment success [1121]; however, these findings need to be externally validated.

Regarding safety concerns, most PD patients treated with CCH experienced at least one mild or moderate adverse reaction localised to the penis (penile haematoma (50.2%), penile pain (33.5%), penile swelling (28.9%) and injection site pain (24.1%)), which resolved spontaneously within 14 days of injection [1122]. The adverse reaction profile was similar after each injection, regardless of the number of injections administered. Serious treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) (0.9%) include penile haematoma and corporeal rupture that require surgical treatment. According to IMPRESS data and the shortened protocol, to prevent serious TEAEs men should be advised to avoid sexual intercourse in the 4 weeks following injection. Recent preliminary data suggest that treatment in the acute phase of the disease can be effective and safe [1079,1116,1117,1123-1125].

In conclusion, CCH is a safe and established treatment for stable-phase disease. More recent evidence suggests that CCH also has a role in affecting the progression of active-phase disease, thus supporting the idea that the indications for CCH use could be expanded, although there is the possibility of a significant placebo effect. It should also be noted that there is a large effect of traction or modelling in controlled studies, while studies reporting on modified protocols have small numbers of patients and are largely uncontrolled. Therefore, patients should be counselled fully on the efficacy of collagenase and the high cost of treatment.

It has been suggested that those patients with severe curvature may also benefit from CCH injections because of a potential downgrading of the penile curvature: a decrease in curvature may allow for a penile plication procedure instead of a plaque incision and grafting procedure, therefore avoiding the more negative impact on erectile function. However, further investigation is needed to validate these initial findings [1079,1117].

The Panel has agreed to keep the whole set of information and recommendations regarding the use of CCH in men with PD despite the official withdrawal of the product from the European market by the company.

Interferon α-2b

Interferon α-2b (IFN-α2b) has been shown to decrease fibroblast proliferation, extracellular matrix production and collagen production by fibroblasts and improve the wound healing process from PD plaques in vitro [1126]. Intralesional injections (5x10^6 units of IFN-α2b in 10 mL saline every 2 weeks over 12 weeks for a total of six injections) significantly improved penile curvature, plaque size and density, and pain compared to placebo. Additionally, penile blood flow parameters are benefited by IFN-α2b [1112,1127,1128]. Regardless of plaque location, IFN-α2b is an effective treatment option. Treatment with IFN-α2b provides a > 20% reduction in curvature in most men with PD, independent of plaque location [1129]. Given the mild adverse effects, which include sinusitis and flu-like symptoms, which can be effectively treated with NSAIDs before IFN-α2b injection, and the moderate strength of data available, IFN-α2b is currently recommended for treatment of stable-phase PD.

Steroids, hyaluronic acid and botulinum toxin (botox)

In the only single-blind, placebo-controlled study with intralesional administration of betamethasone, no statistically significant changes in penile deformity, penile plaque size, and penile pain during erection were reported [1130]. Adverse effects include tissue atrophy, thinning of the skin and immunosuppression [1131]. The effect of hyaluronic acid treatment in patients with PD was investigated in recent studies [1132-1135]. In a non-randomised study, intralesional injection of hyaluronic acid was compared to intralesional verapamil in acute phase PD and significant improvement of pain, curvature and IIEF-15 was observed [1134]. In a RCT, oral administration of hyaluronic acid combined with intralesional injection has been found superior to intralesional injection only and improvement of 7.8±3.9 degrees in curvature and reduction in plaque size of 3.0 mm was observed (LE:1b) [1135]. As only a single study evaluated intralesional botox injections in men with PD, the Panel conclude that there is no robust evidence to support these treatments [1136].

Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP)

In an experimental in-animal study investigating the effect of PRP on PD, no reduction in terms of plaque size has been shown, but the use of PRP resulted in increase in type III/type I collagen ratio and collagen/smooth muscle ratio [1137]. Few studies in humans have evaluated the effect of PRP on penile curvature, plaque size, PDQ and IIEF with low level of evidence (LE:3) (Table 26). Significant improvements were found in penile curvature, and IIEF in two studies. Further studies showed additional improvement in plaque size and PDQ. The effect of PRP in patients with Peyronie’s disease remains to be proven and should currently be considered as being experimental.

Table 26: Studies on PRP in penile curvature and/or PD patients

Author | No of patients | Age (years) | Number of injections | IIEF score | Curvature | Decrease in plaque size | Pain | PDQ |

Virag et al. (2014) [1138] | 13 | 57.5 | 4 (with HA) (2 injections /month) | Improvement in all patients | 30% | 53% | N/A | N/A |

Virag et al. (2017) [1139] | 90 | N/A | 4 (2 injections /month) | +4.1 | %39.65 | -1.11 mm | N/A | improvement |

Marcovici et al. (2018) [1140] | 1 | 54 | 2 | N/A | 20% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Matz et al. (2018) [588] | 11 | 46 | 2.1 | +4.14 | Subjective improvement | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Notsek et al. (2019) [1141] | 59 | N/A | 1 | improvement | 50% | 50% | 84% | N/A |

HA = hyaluronic acid; IIEF = International Index of Erectile Function; N/A = not applicable; PDQ = Peyronie’sdisease questionnaire.

8.2.3.1.3. Topical treatments

Topical verapamil and H-100 Gel

There is no sufficient and unequivocal evidence that topical treatments (verapamil, H-100 Gel [a compound with nicardipine, superoxide dismutase and emu oil] or steroids) applied to the penile shaft, with or without the use of iontophoresis (now known as transdermal electromotive drug administration), result in adequate levels of the active compound within the tunica albuginea [1142-1145]. Therefore, the Panel does not support the use of topical treatments for PD applied to the penile shaft.

Extracorporeal shockwave treatment

The mechanical shear stress provoked by low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave treatment (LI-ESWT) on the treated tissue was deemed to induce neovascularisation and to enhance local blood flow [1087]. The mechanism of action involved in ESWT for PD is still unclear, but there are two hypotheses: (i) SWT works by directly damaging and remodelling the penile plaque; and (ii) SWT increases the vascularity of the area by generating thermodynamic changes resulting in an inflammatory reaction, with increased macrophage activity causing plaque lysis and eventually leading to plaque resorption [1146,1147].

Four RCTs and one meta-analysis [1148-1152] assessed the efficacy of ESWT for PD. Three were sham-controlled trials while one compared ESWT with the combination of ESWT and PDE5I (tadalafil) [1146].

All trials showed positive findings in terms of pain relief, but no effect on penile curvature and plaque size. Inclusion criteria varied widely among studies and further investigation is needed. The results are summarised in Table 27.

Table 27: Efficacy of ESWT in the treatment of PD

Author/Year [Ref] | No. of cases/controls | Inclusion criteria | Comparator | Follow-up | Treatment protocol | Results | Adverse effects |

Palmieri et al. 2009 [1148] | 50 / 50 | PD < 12 mo. No previous treatment | Sham therapy | 6 month | 1 session/week x 4 weeks | Change in IIEF (+5.4points) Pain reduction (-5.1 points) Change in curvature (-1.4º) Plaque size (-0.6 in) | None |

Chitale et al. 2010 [1149] | 16 / 20 | Stable PD > 6 mo. No previous treatment | Sham therapy | 6 month | 1 session/week x 6 weeks. No other parameters mentioned. | Change in IIEF Significant in both groups Pain reduction Significant in both groups Change in curvature N/S Plaque size N/S | None |

Palmieri et al. 2011 [1150] | 50 / 50 | PD < 12 mo. Painful erections Presence of ED | ESWT + tadalafil | 6 month | 1 session/week x 4 weeks 2000 sw, 0.25 mJ/mm2, 4 Hz | Change in IIEF Significant in both groups Pain reduction Significant in both groups Change in curvature N/S Plaque size N/S | None |

Hatzichristodoulou et al. 2013 [1151] | 51 / 51 | Stable PD > 3 mo. Previous unsuccessful oral treatment | Sham therapy | 1 month | 1 session/week x 6 weeks | Change in IIEF N/A Pain reduction (-2.5 points) Change in curvature N/S Plaque size N/S | Ecchymosis 4,9% |

N/A = no assessed; N/S = no significant; IIEF = International index of erectile function; VAS = Visual AnalogicScale; ED = Erectile dysfunction.

Penile traction therapy

In men with PD, potential mechanisms for disease modification with penile traction therapy (PTT) have been described, including collagen remodelling via decreased myofibroblast activity and matrix metalloproteinase up-regulation [1153,1154].

The stated clinical goals of PTT are to non-surgically reduce curvature, enhance girth, and recover lost length, which are attractive to patients with PD. However, clinical evidence is limited due to the small number of patients included (267 in total), the heterogeneity in the study designs, and the non-standardised inclusion and exclusion criteria which make it impossible to draw any definitive conclusions about this therapy [1155-1159].

Most of the included patients will need further treatment to ameliorate their curvature for satisfactory sexual intercourse. Moreover, the effect of PTT in patients with calcified plaques, hourglass or hinge deformities which are, theoretically, less likely to respond to PTT has not been systematically studied. In addition, the treatment can result in discomfort and be inconvenient due to use of the device for an extended period (2-8 hours daily), but has been shown to be tolerated by highly-motivated patients. There were no serious adverse effects, including skin changes, ulcerations, hypo-aesthesia or diminished rigidity [1157,1160].

In conclusion, PTT seems to be effective and safe for patients with PD [1161], but there is still lack of evidence to give any definitive recommendation in terms of monotherapy for PD.

Table 28: Summary of clinical evidence of PTT as monotherapy

Author/year | Study type | Device | No. of patients | Hours of use | Result |

Levine et al. (2008) | Pilot Prospective, uncontrolled | Fast Size® | 10 | 2-8h 6 months | Mean reduction in PC 33% (51º-34º) SPL: + 0.5-2 cm EG: + 0.5-1 cm IIEF: + 5.3 |

Gontero et al. (2009) | Phase II Prospective Uncontrolled | Andropenis® | 15 | > 5h 6 months | Mean reduction in PC: N/S SPL: + 0.8 cm (6 mo) + 1.0 cm (12 mo) |

Martinez-Salamanca et al. (2014) | Prospective, controlled, open label Men in AP | Andropenis® | 96 55 (PD) 41 (NIG) | 6-9h (4.6 h/d) 6 months | Mean reduction in PC: 20º (33º-15º) p < 0.05. SPL: + 1.5 cm (6 mo) EG: + 0.9 cm (6 mo) |

Moncada el al. (2018) | Controlled multicenter trial Men in CP | Penimaster®PRO | 80 41 (PTT) 39 (NIG) | 3-8h 3 months | Mean reduction in PC: 31º (50º-15º). SPL: + 1.8 cm (3 mo) EG: + 0.9 cm (6 mo) IEEF: + 2.5 |

Ziegelmann et al. (2019) [1142] | Randomised, prospective, controlled, single blind study Men in CP and contols 3:1 | Restorex® | 110 | 30-90 min/day 3 months | Mean reduction in PC (3 mo): 13.3º (PTT) + 1.3º (control) SPL: + 1.5 cm (PTT) + 0 cm (control) IIEF: + 4.3 (PTT) -0.7 (control) p = 0.01 |

NIG = non-intervention group; IIEF = International Index of Erectile Function; N/S = Not significant;PD = Peyronie´s Disease; AP = Acute phase; CP = Chronic phase; SPL - Stretched penile length; EG = Erect girth.

Vacuum erection device

Vacuum erection device (VED) therapy results in dilation of cavernous sinuses, decreased retrograde venous blood flow and increased arterial inflow [1162]. Intracorporeal molecular markers are affected by VED application, including decreases in hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, TGF-β1, collagenase, and apoptosis, and increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and α-smooth muscle actin, given their role in the pathogenesis of PD [1163]. Only one clinical study assessed the efficacy of VED therapy in mechanically straightening the penile curvature of PD as monotherapy and further investigation is needed [1164].

8.2.3.1.4. Multimodal treatment

There are some data suggesting that a combination of different oral drugs can be used for treatment of the acute phase of PD. However, there does not seem to be a consensus on which drugs to combine or the optimum drug dosage; nor has there been a comparison of different drug combinations.

A long-term study assessing the role of multimodal medical therapy (injectable verapamil associated with antioxidants and local diclofenac) demonstrated that it is efficacious to treat PD patients. The authors concluded that combination therapy reduced pain more effectively than verapamil alone, making this specific combination treatment more effective compared to monotherapy [1163]. Furthermore, combination protocols including injectable therapies, such as CCH, have been studied in controlled trials. The addition of adjunctive PTT and VED has been described; however, limited data are available regarding its use [1165].

Penile traction therapy has been evaluated as an adjunct therapy to intralesional injections with interferon, verapamil, or CCH [1102,1166,1167]. These studies have failed to demonstrate significant improvements in penile length or curvature, with the exception of one subset analysis identifying a 0.4 cm length increase among men using the devices for > 3 hours/day [1167]. A meta-analysis demonstrated that men who used PTT as an adjunct to surgery or injection therapy for PD had, on average, an increase in stretched penile length (SPL) of 1 cm compared to men who did not use adjunctive PTT. There was no significant change in curvature between the two groups [1168].

Data available on the combined treatment of CCH and the use of VED between injection intervals have shown significant mean improvements in curvature (-17o) and penile length (+0.4 cm) after treatment. However, it is not possible to determine the isolated effect of VED because of a lack of control groups [1119,1168].

Recent data have suggested that combination of PDE5I (sildenafil 25 mg twice daily) after CCH treatment (shortened protocol combined with VED) is superior to CCH alone for improving penile curvature and erectile function. Further studies are necessary to externally validate those findings.

8.2.3.1.5. Summary of evidence for conservative treatment of Peyronie’s disease

Summary of evidence | LE |

Conservative treatment for PD is primarily aimed at treating patients in the early stage of the disease in order to relieve symptoms and prevent progression. | 3c |

There is no convincing evidence supporting oral treatment with acetyl esters of carnitine, vitamin E, potassium para-aminobenzoate (potaba) and pentoxifylline. | 3c |

Due to adverse effects, treatment with oral tamoxifen is no longer recommended. | 3c |

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be used to treat pain in the acute phase. | 4 |

Intralesional treatment with calcium channel antagonists: verapamil and nicardipine are no longer recommended due to contradictory results. | 1b |

Intralesional treatment with Collagenase Clostridium histolyticum showed significant decreases in penile curvature, plaque diameter and plaque length in men with stable disease. | 1b |

Intralesional treatment with interferon may improve penile curvature, plaque size and density, and pain. | 2b |

Intralesional treatment with steroids are no longer recommended due to adverse effects, including tissue atrophy, thinning of the skin and immunosuppression. | 3c |

No robust evidence is available to support treatment with intralesional hyaluronic acid or botulinum toxin. | 3c |

Intralesional hyaluronic acid may be used to improve pain, penile curvature and IIEF scores. | 2b |

Combination of oral and intralesional hyaluronic acid treatment improves penile curvature and plaque size. | 1b |

There is no evidence that topical treatments applied to the penile shaft result in adequate levels of the active compound within the tunica albuginea. | 3c |

The use of iontophoresis is not recommended due to the absence of efficacy data. | 3c |

Extracorporeal shockwave treatment may be offered to treat penile pain, but it does not improve penile curvature and plaque size. | 2b |

Treatment with penile traction therapy alone or in combination with injectable therapy as part of a multimodal approach may reduce penile curvature and increase penile length, although studies have limitations. | 3c |

8.2.3.1.6. Recommendations for non-operative treatment of Peyronie’s disease

Recommendations | Strength rating |

Offer conservative treatment to patients not fit for surgery or when surgery is not acceptable to the patient. | Strong |

Fully counsel patients regarding all available treatment options and outcomes before starting any treatment. | Strong |

Do not offer oral treatment with vitamin E, potassium para-aminobenzoate (potaba), tamoxifen, pentoxifylline, colchicine and acetyl esters of carnitine to treat Peyronie’s disease (PD). | Strong |

Use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to treat penile pain in the acute phase of PD. | Strong |

Use extracorporeal shockwave treatment (ESWT) to treat penile pain in the acute phase of PD. | Weak |

Use phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors to treat concomitant erectile dysfunction or if the deformity results in difficulty in penetrative intercourse in order to optimise penetration. | Weak |

Offer intralesional therapy with interferon alpha-2b to patients with stable curvature dorsal or lateral > 30o seeking a minimal invasive procedure. | Strong |

Offer intralesional therapy with Collagenase Clostridium Histolyticum to patients with stable PD and dorsal or lateral curvature > 30o, who request non-surgical treatment, although the placebo effects are high. | Strong |

Do not offer intralesional treatment with steroids to reduce penile curvature, plaque size or pain. | Strong |

Do not use intralesional platelet-rich plasma or hyaluronic acid, either alone or in combination with oral treatment, to reduce penile curvature, plaque size or pain outside the confines of a clinical trial. | Weak |

Do not offer ESWT to improve penile curvature and reduce plaque size. | Strong |

Offer penile traction devices and vacuum devices to reduce penile deformity or as part of a multimodal therapy approach, although outcome data is limited. | Weak |

8.2.3.2. Surgical treatment

Although conservative treatment for PD may resolve painful erections in most men, only a small percentage experience significant straightening of the penis. The aim of surgery is to correct curvature and allow penetrative intercourse. Surgery is indicated in patients with significant penile deformity and difficulty with intercourse associated with sexual bother. Patients must have a stable disease for 3-6 months (or more than 9-12 months after onset of PD) [1062,1071,1169]. In addition to this requirement, there are other situations that may precipitate an indication for surgery, such as failed conservative or medical therapies, extensive penile plaques, or patient preference, when the disease is stable [1170,1171].

Before considering reconstructive surgery, it is recommended to document the size and location of penile plaques, the degree of curvature, complex deformities (hinge or hourglass), the penile length and the presence or absence of ED. The potential aims and risks of surgery should be fully discussed with the patient so that he can make an informed decision [1169]. Specific issues that should be mentioned during this discussion are: risk of penile shortening; ED, penile numbness; and delayed orgasm, the risk of recurrent curvature, potential for palpation of knots and stitches underneath the skin, potential need for circumcision at the time of surgery, residual curvature and the risk of further penile wasting with shortening procedures [1071,1172]. Selection of the most appropriate surgical intervention is based on penile length assessment, curvature severity and erectile function status, including response to pharmacotherapy in cases of ED [1071]. Patient expectations from surgery must also be included in the pre-operative assessment. The main objective of surgery is to achieve a “functionally straight” penis, and this must be fully understood by the patient to achieve the best possible satisfaction outcomes after surgery [1169,1173].

Three major types of reconstruction may be considered for PD: (i) tunical shortening procedures; (ii) tunical lengthening procedures; and, (iii) penile prosthesis implantation, with or without straightening techniques in the presence of concomitant ED and residual curvature [1174,1175].

Tunical shortening procedures achieve straightening of the penis by shortening the longer, convex side of the penis to make it even with the contralateral side. Tunical lengthening procedures are performed on the concave side of the penis after making an incision or partial excision of the plaque, with coverage of the defect with a graft. Although tunical lengthening procedures rarely lead to long-term penile length gain, they aim to minimise penile shortening caused by plication of the tunica albuginea, and correct complex deformities. In practice, tunical lengthening procedures are often combined with penile plication or shortening procedures to correct residual curvature [1176]. In patients with PD and ED not responding to medical therapy, penile prosthesis implantation can be considered with correction of the curvature including adjunct techniques (modelling, plication or incision/excision with grafting).

Penile degloving with associated circumcision (as a means of preventing post-operative phimosis) should be considered the standard approach for all types of procedures, although modifications have been described. Only one study has suggested that circumcision is not always necessary (e.g., in cases where the foreskin is normal pre-operatively) [1177]. Non-degloving techniques have been described that have been shown to prevent ischaemia and lymphatic complications after subcoronal circumcision [1178,1179].

There are no standardised questionnaires for the evaluation of surgical outcomes. Data from well-designed prospective studies are scarce, with low levels of evidence. Data are mainly based on retrospective single-centre studies, typically non-comparative and non-randomised, or on expert opinion [1071,1180]. Therefore, surgical outcomes must be treated with caution.

8.2.3.2.1. Tunical shortening procedures

For men with good erectile function, adequate penile length, without complex deformities, such as an hourglass or hinge type narrowing abnormality, and non-severe curvature, a tunical shortening procedure can be considered an appropriate surgical approach. Numerous different techniques have been described, although they can be classified as excisional, incisional and plication techniques.

In 1965, Nesbit was the first to describe the removal of tunical ellipses opposite to the point of maximum curvature with a non-elastic corporal segment to treat CPC [1181]. Thereafter, this technique became a successful treatment option for PD-associated penile curvature [1182]. This operation is based on a 5-10 mm transverse elliptical excision of the tunica albuginea or ~1 mm for each 10° of curvature. The overall short- and long-term results of the Nesbit operation are excellent [1183-1187]. Some modifications of the Nesbit procedure have been described (partial thickness shaving instead of conventional excision; underlapped U incision) with similar results, although these are in non-randomised studies [1188-1192].

The Yachia technique is based on a completely different concept, as it utilises the Heinke-Mikowitz principle for which a longitudinal tunical incision is closed transversely to shorten the convex side of the penis. This technique, initially described by Lemberger in 1984, was popularised by Yachia in 1990, when he reported a series of 10 cases [1193-1198].

Pure plication techniques are simpler to perform. They are based on single or multiple plications performed without making excisions or incisions to the tunical albuginea, to limit the potential damage to the veno-occlusive mechanism [1073,1199-1215]. Another modification has been called the ’16-dot’ technique that consists of application of two pairs of parallel Essed-Schroeder plications tensioned more or less depending on the degree of curvature [1192,1216-1218]. The use of non-absorbable sutures or longer-lasting absorbable sutures may reduce recurrence of the curvature (Panel expert opinion). Results and satisfaction rates similar with both incision/excision techniques.

In general, using these tunical shortening techniques, complete penile straightening is achieved in > 85% of patients. Recurrence of the curvature and penile hypo-aesthesia is uncommon (~10%) and the risk of post-operative ED is low. Penile shortening is the most commonly reported outcome of these procedures. Shortening of 1-1.5 cm has been reported for 22-69% of patients, which is rarely the cause of post-operative sexual dysfunction and patients may perceive the loss of length as greater than it actually is. It is therefore strongly advisable to measure and document the penile length peri-operatively, both before and after the straightening procedure, whatever the technique used (Table 29).

As mentioned above, there are multiple techniques with small modifications and all of them have been reported in retrospective studies, most of them without comparison between techniques and therefore the level of evidence is not sufficient to recommend one particular method over another.

Table 29: Results of tunical shortening procedures for PD (data from different, non-comparable studies)

Tunical shortening procedures | |||||

Nesbit | Modified Nesbit | Yachia | 16-dot / mod16-dot | Simple plication | |

No. of patients/studies | 652 / 4 | 387 / 5 | 150 / 6 | 285 / 5 | 1068 / 18 |

Significant penile shortening (%)*† | 8.7% (5-39) | 3.2% (0-13) | 3.5% (0-10) | 5.9% (0-6) | 8.9% (0-55) |

Any penile shortening (%)* | 21.8% (9-39) | 58.% (23-74) | 69% (47-97) | 44.6% (40-52) | 33.4% (0-90) |

Penile straightening (%)* | 88.5% (86-100) | 97.6% (92-100) | 95.5% (93-100) | 96.9% (95-100) | 94.7% (85-100) |

Post-operative de novo ED (%)* | 6.9% (0-17) | 3% (0-13) | 9.6% (0-13) | 3.8% (0-13) | 8.1% (0-38) |

Penile hypoesthesia (%)* | 11. 8% (2-60) | 5.6% (0-31) | 1% (0-3) | 8.2% (6-13) | 9% (0-47) |

Overall satisfaction (%)* | 83.5% (76-88) | 95.4% (87-100) | 86.8% (78-100) | 94% (86-100) | 86.4% (52-100) |

Follow-up (months)* | (69-84) | (19-42) | (10-24) | (18-71) | (12-141) |

*Data are expressed as weighted average. † Defined as > 30 degrees of curvature. Ranges are in parentheses.ED = Erectile dysfunction.

8.2.3.2.2. Tunical lengthening procedures

Tunical lengthening surgery is preferable in patients with significant penile shortening, severe curvature and/or complex deformities (hourglass or hinge) but without underlying ED. The definition of severe curvature has been proposed to be > 60o, although no studies have validated this threshold. However, it may be used as an informative guide for patients and clinicians in surgical counselling and planning, although there is no unanimous consensus based on the literature that such a threshold can predict surgical outcomes (Panel expert consensus opinion). On the concave side of the penis, at the point of maximum curvature, which usually coincides with the location of the plaque, an incision is made, creating a defect in the albuginea that is covered with a graft. Complete plaque removal or plaque excision may be associated with higher rates of post-operative ED due to venous leak, but partial excision in cases of florid calcification may be permissible [1219,1220]. Patients who do not have pre-operative ED should be informed of the significant risk of post-operative ED of up to 50% [1172].

Since 1974, when the first study using dermal grafting to treat PD was published [1221], a large number of different grafts have been used. The ideal graft should be resistant to traction, easy to suture and manipulate, flexible (not too much, to avoid aneurysmal dilations), readily available, cost-effective, and morbidity should be minimal, especially when using autografts. No graft material meets all of these requirements. Moreover, the studies performed did not compare different types of grafts and biomaterials and were often single-centre retrospective studies so there is not a single graft that can be recommended for surgeons [1222]. Grafting procedures are associated with long-term ED rates as high as 50%. The presence of pre-operative ED, the use of larger grafts, age > 60 years, and ventral curvature are considered poor prognostic factors for good functional outcomes after grafting surgery [1175]. Although the risk for penile shortening appears to be less than that compared to the Nesbit, Yachia or plication procedures, it is still an issue and patients must be informed accordingly [1174]. Higher rates (3-52%) of penile hypo-aesthesia have also been described after these operations, as damage of the neurovascular bundle with dorsal curves (in the majority) is inevitable. A recent prospective study showed that 21% of patients had some degree of sensation loss at 1 week, 21% at 1 month, 8% at 6 months, and 3% at 1 year [1223]. The use of geometric principles introduced by Egydio may help to determine the exact site of the incision, and the shape and size of the defect to be grafted [1224].

Grafts for PD surgery can be classified into four types (Table 30) [1063]:

- Autografts: taken from the individual himself, they include the dermis, vein, temporalis fascia, fascia lata, tunica vaginalis, tunica albuginea and buccal mucosa.

- Allografts: also of human origin but from a deceased donor, including the pericardium, fascia lata and dura mater.

- Xenografts: extracted from different animal species and tissues, including bovine pericardium, porcine small intestinal submucosa, bovine and porcine dermis, and TachoSil® (matrix of equine collagen).

- Synthetic grafts: these include Dacron® and Gore-Tex®.

All the autologous grafts have the inconvenience of possible graft harvesting complications. Dermal grafts are commonly associated with veno-occlusive ED (20%) due to lack of adaptability, so they have not been used in contemporary series [1221,1222,1225-1235]. Vein grafts have the theoretical advantage of endothelial-to-endothelial contact when grafted to underlying cavernosal tissue. The saphenous vein has been the most commonly used vein graft [1236-1251]. For some extensive albuginea defects, more than one incision may be needed. Tunica albuginea grafts have perfect histological properties but have some limitations: the size that can be harvested, the risk of weakening penile support and making future procedures (penile prosthesis implantation) more complicated [1252-1254]. Tunica vaginalis is easy to harvest and has little tendency to contract due to its low metabolic requirements, although better results can be obtained if a vascular flap is used [1255-1259]. Under the pretext that by placing the submucosal layer on the corpus cavernosum the graft feeds on it and adheres more quickly, the buccal mucosal graft has recently been used with good short-term results [1260-1266].

Cadaveric dura mater is no longer used due to concerns about the possibility of infection [1267,1268]. Cadaveric pericardium (Tutoplast®) offers good results by coupling excellent tensile strength and multidirectional elasticity/expansion by 30% [1156,1220,1231,1269,1270]. Cadaveric or autologous fascia lata or temporalis fascia offers biological stability and mechanical resistance [1271-1273].

Xenografts have become more popular in recent years. Small intestinal submucosa (SIS), a type I collagen-based xenogenic graft derived from the submucosal layer of the porcine small intestine, has been shown to promote tissue-specific regeneration and angiogenesis, and supports host cell migration, differentiation and growth of endothelial cells, resulting in tissue structurally and functionally similar to the original [1274-1283]. As mentioned above, pericardium (bovine, in this case) has good traction resistance and adaptability, and good host tolerance [1251,1284-1287]. Grafting by collagen fleece (TachoSil®) in PD has some major advantages such as decreased operating times, easy application and an additional haemostatic effect [1288-1293].

It is generally recommended that synthetic grafts, including polyester (Dacron®) and polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-Tex®) are avoided, due to increased risks of infection, secondary graft inflammation causing tissue fibrosis, graft contractures, and possibility of allergic reactions [1196,1294-1297].

Some authors recommend post-operative penile rehabilitation to improve surgical outcomes. Some studies have described using VED and PTT to prevent penile length loss of up to 1.5 cm [1298]. Daily nocturnal administration of PDE5I enhances nocturnal erections, encourages perfusion of the graft, and may minimise post-operative ED [1299]. Massages and stretching of the penis have also been recommended once wound healing is complete.

Table 30: Results of tunical lengthening procedures for PD (data from different, non-comparable studies)

Year of publication | No. of patients / studies | Success (%)* | Penile shortening (%)* | De novo ED (%)* | Follow-up (mo)* | |

Autologous grafts | ||||||

Dermis | 1974-2019 | 718 / 12 | 81.2% (60-100) | 59.9% (40-75) | 20.5% (7-67) | (6-180) |

Vein grafts | 1995-2019 | 690 / 17 | 85.6% (67-100) | 32.7% (0-100) | 14.8% (0-37) | (12-120) |

Tunica albuginea | 2000-2012 | 56 / 3 | 85.2% (75-90) | 16.3% (13-18) | 17.8% (0-24) | (6-41) |

Tunica vaginalis | 1980-2016 | 76 / 5 | 86.2% (66-100) | 32.2% (0-83) | 9.6% (0-41) | (12-60) |

Temporalis fascia / Fascia lata | 1991-2004 | 24 / 2 | 100% | 0% | 0% | (3-10) |

Buccal mucosa | 2005-2016 | 137 / 7 | 94.1% (88-100) | 15.2% (0-80) | 5.3% (0-10) | (12-45) |

Allografts (cadaveric) | ||||||

Pericardium | 2001-2011 | 190 / 5 | 93.1% (56-100) | 23.1% (0-33) | 37.8% (30-63) | (6-58) |

Fascia lata | 2006 | 14 / 1 | 78.6% | 28.6% | 7.1% | 31 |

Dura matter | 1988-2002 | 57 / 2 | 87.5% | 30% | 17.4% (15-23) | (42-66) |

Xenografts | ||||||

Porcine SIS | 2007-2018 | 429 / 10 | 83.9% (54-91) | 19.6% (0-66) | 21.9% (7-54) | (9-75) |

Bovine pericardium | 2002-2020 | 318 / 6 | 87.4% (76.5-100) | 20.1% (0-79.4) | 26.5% (0-50) | (14-67) |

Bovine dermis | 2016 | 28 / 1 | 93% | 0% | 25% | 32 |

Porcine dermis | 2020 | 19 / 1 | 73.7% | 78.9% | 63% | 85 |

TachoSil® | 2002-2020 | 529 / 7 | 92.6% (83.3-97.5) | 13.4% (0-93) | 13% (0-21) | (0-63) |

*Data are expressed as weighted average. Ranges are in parentheses.

ED = Erectile dysfunction; SIS = Small intestinal submucosa.

The results of tunical shortening and lengthening approaches are presented in Tables 29 and 30. It must be emphasised that there have been no RCTs comparing surgical outcomes in PD. The risk of ED seems to be greater for penile lengthening procedures [1071]. Recurrent curvature is likely to be the result of failure to wait until the disease has stabilised, re-activation of the condition following the development of stable disease, or the use of early re-absorbable sutures (e.g., Vicryl) that lose their tensile strength before fibrosis has resulted in acceptable strength of the repair. Accordingly, it is recommended that only non-absorbable sutures or slowly re-absorbed absorbable sutures (e.g., polydioxanone) should be used. With non-absorbable sutures, the knot should be buried to avoid troublesome irritation of the penile skin, but this issue may be alleviated by the use of slowly re-absorbable sutures (e.g., polydioxanone) [1183]. Penile numbness is a potential risk of any surgical procedure, involving mobilisation of the dorsal neurovascular bundle. This is usually a temporary neuropraxia, due to bruising of the dorsal sensory nerves. Given that the usual deformity is a dorsal deformity, the procedure most likely to induce this complication is a lengthening (grafting) procedure, or the association with (albeit rare) ventral curvature [1174].

8.2.3.2.3. Penile prosthesis

Penile prosthesis (PP) implantation is typically reserved for the treatment of PD in patients with concomitant ED not responding to conventional medical therapy (PDE5I or intracavernous injections of vasoactive agents) [1071]. Although inflatable prostheses (IPPs) have been considered more effective in the general population with ED, some studies support the use of malleable prostheses in these patients with similar satisfaction rates [1071,1302,1303]. The evidence suggests that there is no real difference between the available IPPs [1304]. Surgeons can and should advise on which type of prosthesis best suits the patient but it is the patient who should ultimately choose the prosthesis to be implanted [673].

Most patients with mild-to-moderate curvature can expect an excellent outcome simply by cylinder insertion [1249,1305]. If the curvature after placement of the prosthesis is < 30° no further action is indicated, since the prosthesis itself will act as an internal tissue expander to correct the curvature during the subsequent

6-9 months. If, the curvature is > 30°, the first-line treatment would be modelling with the prosthesis maximally inflated (manually bent on the opposite side of the curvature for 90 seconds, often accompanied by an audible crack) [1306,1307]. If, after performing this manoeuvre, a deviation > 30° persists, subsequent steps would be incision with collagen fleece coverage or without (if the defect is small, it can be left uncovered) or plaque incision and grafting [1308-1313]. However, the defect may be covered if it is larger, and this can be accomplished using grafts commonly used in grafting surgery (described above) which prevent herniation and recurrent deformity due to the scarring of the defect [1314,1315]. The risk of complications (infection, malformation, etc.) is not increased compared to that in the general population. However, a small risk of urethral perforation (3%) has been reported in patients with ‘modelling’ over the inflated prosthesis [1306].

In selected cases of end-stage PD with ED and significant penile shortening, a lengthening procedure, which involves simultaneous PP implantation and penile length restoration, such as the “sliding” technique has been considered [1316]. However, the “sliding” technique is not recommended due to reported cases of glans necrosis because of the concomitant release of the neurovascular bundle and urethra, new approaches for these patients have been recently described, such as the MoST (Modified Sliding Technique), MUST (Multiple-Slit Technique) or MIT (Multiple-Incision Technique) techniques, but these should only be used by experienced high-volume surgeons and after full patient counselling [1317-1320].

While patient satisfaction after IPP placement in the general population is high, satisfaction rates have been found to be significantly lower in those with PD. Despite this, depression rates decreased after surgery in PD patients (from 19.3%-10.9%) [1321]. The main cause of dissatisfaction after PPI in the general population shortening; therefore, patients with PD undergoing PP surgery must be counselled that the prostheses are not designed to restore the previous penile length [1321,1322].

8.2.3.2.4. Summary of evidence for surgical treatment of Peyronie’s disease

Summary of evidence | LE |

Surgery for PD should only be offered in patients with stable disease with functional impairment. | 2b |

In patients with concomitant PD and ED without response to medical treatment, penile prosthesis implantation with or without additional straightening manoeuvres is the technique of choice. | 2a |

In other cases, factors such as penile length, rigidity of erection, degree of curvature, presence of complex deformities and patient choice must be taken into account to decide on a tunical shortening or lengthening technique. | 3 |

8.2.3.2.5. Recommendations for surgical treatment of penile curvature

Recommendations | Strength rating |

Perform surgery only when Peyronie’s disease (PD) has been stable for at least three months (without pain or deformity deterioration), which is usually the case after twelve months from the onset of symptoms, and intercourse is compromised due to the deformity. | Strong |

Assess penile length, curvature severity, erectile function (including response to pharmacotherapy in case of erectile dysfunction [ED]) and patient expectations prior to surgery. | Strong |

Use tunical shortening procedures as the first treatment option for congenital penile curvature and for PD with adequate penile length and rigidity, less severe curvatures and absence of complex deformities (hourglass or hinge). The type of procedure used is dependent on surgeon and patient preference, as no procedure has proven superior to its counterparts. | Weak |

Use tunical lengthening procedures for patients with PD and normal erectile function, without adequate penile length, severe curvature or presence of complex deformities (hourglass or hinge). The type of graft used is dependent on the surgeon and patient factors, as no graft has proven superior to its counterparts. | Weak |

Use the sliding techniques with extreme caution, as there is a significant risk of life changing complications (e.g., glans necrosis). | Strong |

Do not use synthetic grafts in PD reconstructive surgery. | Strong |

Use penile prosthesis implantation, with or without any additional straightening procedures (modelling, plication, incision or excision with or without grafting), in PD patients with ED not responding to pharmacotherapy. | Strong |

8.2.3.3. Treatment algorithm

As mentioned above, in the active phase of the disease, most therapies are experimental or with low evidence. In cases of pain, LI-ESWT, tadalafil and NSAIDs can be offered. In cases of curvature or penile shortening, traction therapy has demonstrated good responses.

When the disease has stabilised, intralesional treatments (mainly CCH) or surgery may be used. Intralesional treatments may reduce the indications for surgery or change the technique to be performed but only after full patient counselling, which should also include a cost-benefit discussion with the patient.

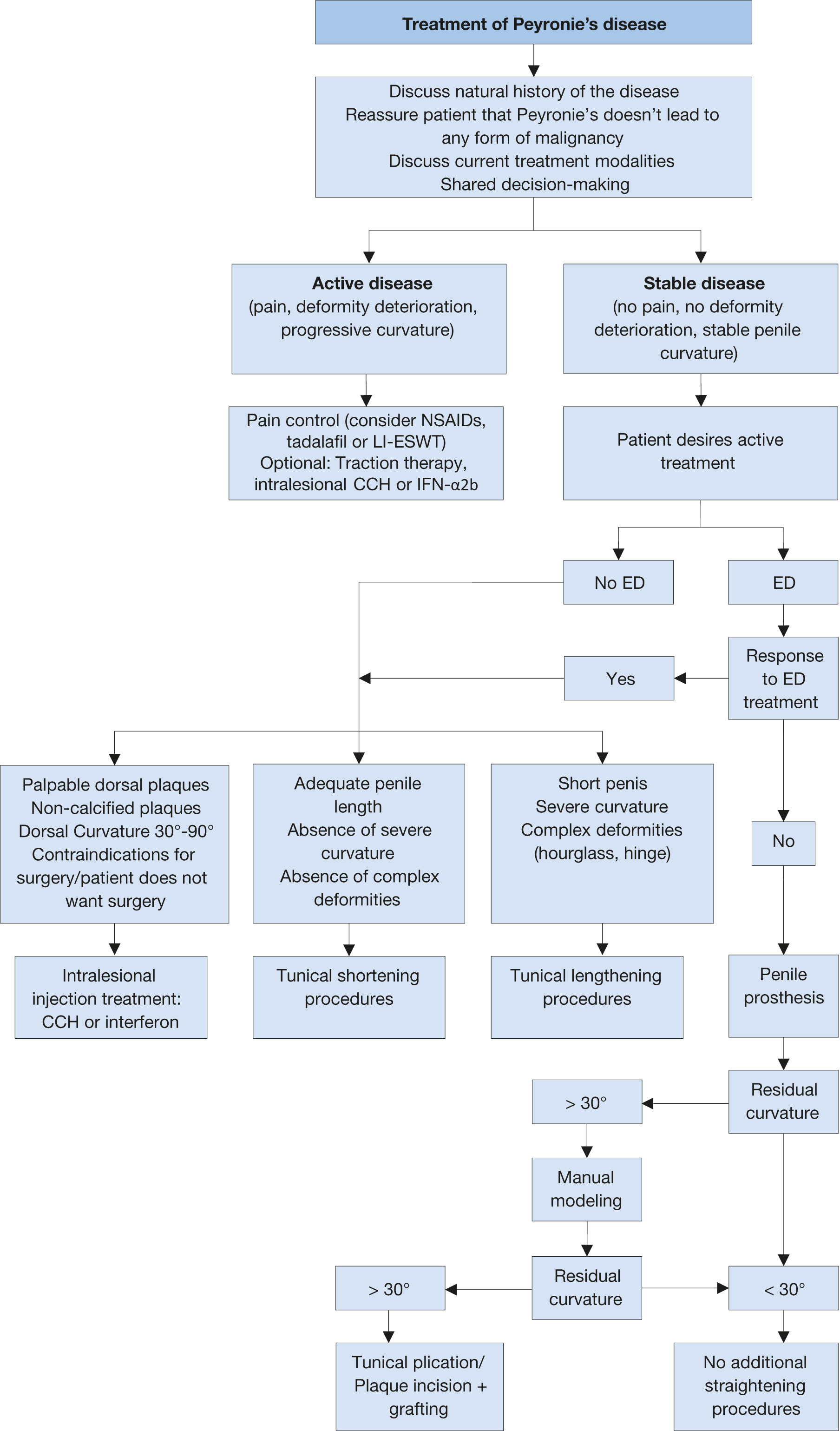

The decision on the most appropriate surgical procedure to correct penile curvature is based on pre-operative assessment of penile length, the degree of curvature and erectile function status. In non-complex and non-severe deformities, tunical shortening procedures are acceptable and are usually the method of choice. This is typically the case for CPC. If severe curvature or complex deformation is present (hourglass or hinge), or if the penis is significantly shortened in patients with good erectile function (preferably without pharmacological treatment), then tunical lengthening is feasible, using any of the grafts previously mentioned. If there is concomitant ED, which is not responsive to pharmacological treatment, the best option is the implantation of a penile prosthesis, with or without a straightening procedure over the penis (modelling, plication, incision or excision with or without grafting). The treatment algorithm is presented in Figure 11.

Figure 11: Treatment algorithm for Peyronie’s disease ED = erectile dysfunction; LI-ESWT = Low-intensity extracorporeal shockwave treatment; NSAIDs = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; CCH = Collagenase Clostridium histolyticum; IFN-α2b = Interferon-α2b.

ED = erectile dysfunction; LI-ESWT = Low-intensity extracorporeal shockwave treatment; NSAIDs = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; CCH = Collagenase Clostridium histolyticum; IFN-α2b = Interferon-α2b.